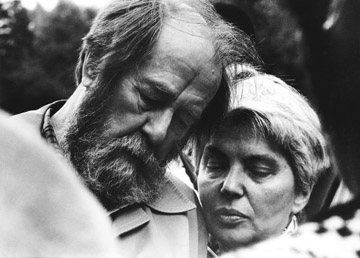

Every teen has his idols; Alexandr Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008), famous author who was imprisoned for years under the Soviet regime, was one of mine.

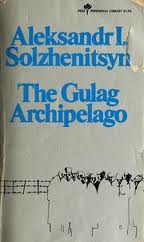

I bought volume one of his grim, great Gulag Archipelago (Prison Islands) trilogy, and it spent the summer of 1974 with me. I sat in our old GMC grain truck during harvest, waiting for the combine to make its way toward me with a load of wheat and reading about another dark, cold, and barren world as far from the warmth of Montana Augusts as it could be.  The book grew dirty (grease, I think, from the combine) and dog-eared; I had to re-read parts of it to fathom not just the violence and structural evils Soviet communism created, but also the utter poverty and suffering endured by human beings. These sometimes-nameless men (though many were named) often turned toward God in their forced ascetic worlds. For myself who had just met Christ a year before the book’s publication that spiritual spark amidst the horrors of history made these men (including Solzhenitsyn) not mere heroes but saints.

The book grew dirty (grease, I think, from the combine) and dog-eared; I had to re-read parts of it to fathom not just the violence and structural evils Soviet communism created, but also the utter poverty and suffering endured by human beings. These sometimes-nameless men (though many were named) often turned toward God in their forced ascetic worlds. For myself who had just met Christ a year before the book’s publication that spiritual spark amidst the horrors of history made these men (including Solzhenitsyn) not mere heroes but saints.

The Zek — abbreviation for a political prisoner in the USSR — lived in an astonishingly narrow world. It was one that fascinated me. True, my childhood as an American insured that I’d been raised to look at the Soviet Union as what Reagan would call “the Evil Empire.” (Solzhenitsyn’s later words against the West’s own version of Evil Empire were dealt with as the West usually deals with such voices… with gentle mockery and/or haughty dismissal.) But through The Gulag Archipelago I discovering that the prison system in Soviet Russia rivaled and surpassed the evils of those created by the Czars. Dostoevsky (also a prisoner himself and nearly executed before the Czar pardoned him) painted a picture of the latter, Dickens and Hugo had respectively (Tale of Two Cities, Les Miserables) explored prisoners’ oppression. But no one ever portrayed in literature the life of a prisoner the way Solzhenitsyn did, as one with the total context of history. No one ever had tied that prisoner’s almost unbearable personal world to all the political and historic forces creating such a life for their victim. Yes, as a documentary of sorts…. but far more than that.

Solzhenitsyn speaks as one who is there, who sees, and whose moral vision spares nothing and no one. Including himself:

“If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart? During the life of any heart this line keeps changing place; sometimes it is squeezed one way by exuberant evil and sometimes it shifts to allow enough space for good to flourish. One and the same human being is, at various ages, under various circumstances, a totally different human being. At times he is close to being a devil, at times to sainthood. But his name doesn’t change, and to that name we ascribe the whole lot, good and evil.”

And this:

“Every man always has handy a dozen glib little reasons why he is right not to sacrifice himself.”

I began reading more, including The First Circle and Cancer Ward. After joining the Jesus People USA community in 1977, I accompanied a few JPUSA friends to a small “art theater” showing of the 1970 film version of Sozhenitsyn’s 1962 book, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. (I had to read the book after seeing this movie.) The book, cited by some as helping bring down the Soviet system, was initially allowed publication in Soviet Russia because it targeted the Stalinist era. Khrushchev, the USSR’s leader in the early sixties, thought it a blow against Stalin’s supporters. It was instead a hint of what would come. Ivan Denisovich was one voice, perhaps modeled on Solzhenitsyn’s own eight-year stretch as a political prisoner. But The Gulag Archipelago told the tale of hundreds, thousands, perhaps millions. And it used first-person testimony and historical documentation to reveal that Stalin’s Russia was not the creator of the Gulag; Lenin, the father of communist Russia, was the source.

So as I sat with my friends watching a day in that one prisoner, Ivan’s, life I found myself transported again into Solzhenitsyn’s world of cold, of poverty, of oppression, and of occasional but unmistakable spiritual luminosity.

I will always remember and revere Alexandr Solzhenitsyn as the man who introduced me not merely to dehumanization via a cold, barren ideology but also to the individuals who were — often through faith — able to overcome that dehumanization and shine like stars in a frozen Siberian sky. I will also never forget the words he spoke against our own Empire of Materialism and shallowness, an Empire that currently has the largest Gulag Archipelago on the face of the earth.

Solzhenitsyn warned us in the Gulag, “The whole raison d’etre of serfdom and the Archipelago is one and the same: these are the social structures for the ruthless enforced utilisation of the free-of-cost work of millions of slaves.” The USSR’s Gulag was an economic machine of fairly primitive variety, the prisoners themselves providing the manual labor to turn the Soviet machinery’s gears; ours is far more sophisticated, the prisoners being warehoused in deep and bitter storage and the prison machinery itself being the economic engine for capitalism to thrive. But our only real innovation is to create a system in which the prisoner does not even get the opportunity to leave his or her cell; the prisoner as economic stimulus almost literally is cannibalized by the Empire’s machinery of Mammon.

-=-

(Below is a link to the first 10 minutes or so of the 1970 film version of A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.)