Violence against blacks by police. Yesterday, one black man murdered in Minnesota and one murdered in Louisiana. Many yesterdays here in Chicago. Not a time to hear my own white male voice. Where race is concerned this is doubly true. I thought I’d simply post four black novelists’ words here instead. Need it be said that black fiction is often truer than white fact?

These men (even female black novelists seem to write less about such confrontation) are older novelists. I’m an older male. These voices are the ones that spoke to me when I was young and awakened me to many things. They continue to speak to me. So while Ta Nehisi Coates and other younger voices also speak truth to power, I turn to my old tutors. (Please… anyone who would like to add quotes from their own teachers… or own experiences… do so in the comments!)

First up….

James Baldwin

And we had three milk shakes on the corner, and Levy shook hands, and left us, saying that he had to get home to his wife and kids – two boys, one aged two, one aged three and a half. But before he left us, he said, “Look. I told you not to worry about the neighbors. But watch out for the cops. They’re murder.”

One of the most terrible, most mysterious things about a life is that a warning can be heeded only in retrospect: too late.

— James Baldwin, If Beale Street Could Talk

MOTHER HENRY: You’re going to make yourself sick. You’re going to make yourself sick with hatred.

RICHARD: No, I’m not. I’m going to make myself well. I’m going to make myself well with hatred—what do you think of that?

MOTHER HENRY: It can’t be done. It can never be done. Hatred is a poison, Richard.

RICHARD: Not for me. I’m going to learn how to drink it—a little every day in the morning, and then a booster shot late at night. I’m going to remember everything. I’m going to keep it right here, at the very top of my mind. I’m going to remember Mama, and Daddy’s face that day, and Aunt Edna and all her sad little deals and all those boys and girls in Harlem and all them pimps and whores and gangsters and all them cops. And I’m going to remember all the dope that’s flowed through my veins. I’m going to remember everything—the jails I been in and the cops that beat me and how long a time I spent screaming and stinking in my own dirt, trying to break my habit. I’m going to remember all that, and I’ll get well. I’ll get well.

MOTHER HENRY: Oh, Richard. Richard. Richard.

RICHARD: Don’t Richard me. I tell you, I’m going to get well.

(He takes a small, sawed-off pistol from his pocket.)

MOTHER HENRY: Richard, what are you doing with that gun?

RICHARD: I’m carrying it around with me, that’s what I’m doing with it. This gun goes everywhere I go.

MOTHER HENRY: How long have you had it?

RICHARD: I’ve had it a long, long time.

MOTHER HENRY: Richard—you never—?

RICHARD: No. Not yet. But I will when I have to. I’ll sure as hell take one of the bastards with me.

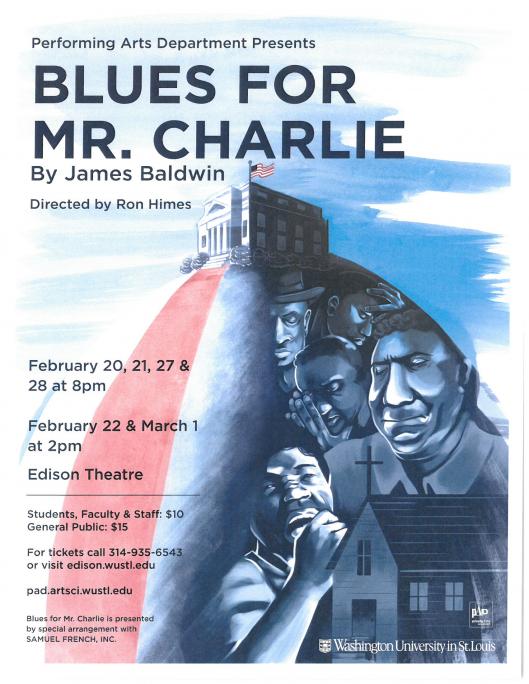

–James Baldwin Blues for Mister Charlie

The cops say!” said my father.

I had seen the cops in the store many times; they had always been perfectly friendly with the owner. “The store is closed,” I said. I went over to my mother. “Mama—Mama—what they going to do if they find Caleb?” My mind had stopped, stuck, screaming, on the faces of white cops.

“They going to take him away,” she said.

I looked at my father. “But Caleb don’t steal! Caleb never stole nothing in his whole life!” My father said nothing. We heard footsteps on the stairs. Not one of us moved. But the steps stopped just below our landing. Then I realized that I would have to find Caleb and tell him not to come home. I stuffed my money in my pockets—maybe he would need it. I said, “I’ll be right back,” and I ran out of the house and down the stairs. I ran down those stairs faster than Caleb ever had, and into the startling wind of the street. Everything was new, everything was evil, every house was dangerous. The people all were strangers. I do not think I saw them. And yet, something cautioned me not to run too fast; something cautioned me to dissemble my distress; something cautioned me to look, to look about me, before I moved. I stood on my stoop and I looked toward the dreadful river. Only small boys were playing there. Across the street, there were ladies in windows and men on stoops; and up the street, more men and boys and ladies, and no cops. I touched the money in my pockets—I don’t know why; perhaps I wanted everyone to believe that I had been sent to the store. And then I started walking, out of the block, toward Miss Mildred’s house. But I did not go down the avenue because I was afraid to pass the store.

–James Baldwin Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone

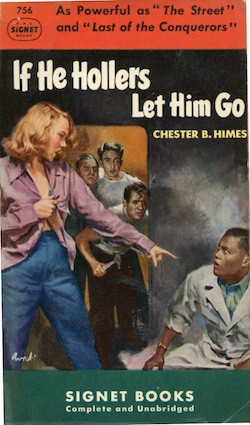

Chester Himes

The president of the shipyard said, ‘Niggers can take it as long as you give it to them.’ Somebody laughed and I looked around and saw two policemen standing by a squad car to one side nudging each other and laughing. There was no one else on the street. The other peckerwood said, ‘It ain’t right to beat this nigger like that. What we beating this nigger for anyway?’ The cops stopped laughing and looked at him and the president of the shipyard got hard and said, ‘Continue! It’s an order!’ So they started beating me again and I was hoping I would become unconscious but I couldn’t.

Then I felt myself rolling over in bed, struggling with the covers, but I couldn’t wake up, and the dream kept right on with the two peckerwoods beating me not quite to death. Then two old coloured couples in working clothes on their way to work came up and the peckerwoods stopped beating me and the cops came up and stood over me with their hands on their guns and their chins stuck out as if they were scared I might get up and hurt somebody. The coloured people looked at the peckerwoods with dull hatred and then the president of the shipyard smiled at them and said, ‘There should be something done about this,’ and they looked at him gratefully and said: ‘Yassuh, it’s a shame to go beating a man like that,’ and the president of the shipyard said, ‘All of us responsible white people are trying to keep these things from taking place, but you boys must help us.’ I tried to tell the coloured people what he had been doing before they came but my voice wouldn’t come out and they just looked at him as if he was a good kind god and said, ‘Yassuh, some of these heah boys do git out of their place, but usses don’t cause no trouble at all.

Then I felt myself rolling over in bed, struggling with the covers, but I couldn’t wake up, and the dream kept right on with the two peckerwoods beating me not quite to death. Then two old coloured couples in working clothes on their way to work came up and the peckerwoods stopped beating me and the cops came up and stood over me with their hands on their guns and their chins stuck out as if they were scared I might get up and hurt somebody. The coloured people looked at the peckerwoods with dull hatred and then the president of the shipyard smiled at them and said, ‘There should be something done about this,’ and they looked at him gratefully and said: ‘Yassuh, it’s a shame to go beating a man like that,’ and the president of the shipyard said, ‘All of us responsible white people are trying to keep these things from taking place, but you boys must help us.’ I tried to tell the coloured people what he had been doing before they came but my voice wouldn’t come out and they just looked at him as if he was a good kind god and said, ‘Yassuh, some of these heah boys do git out of their place, but usses don’t cause no trouble at all.

— Chester Himes If He Hollers Let Him Go

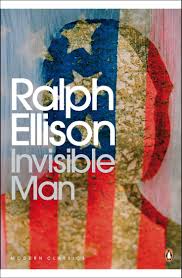

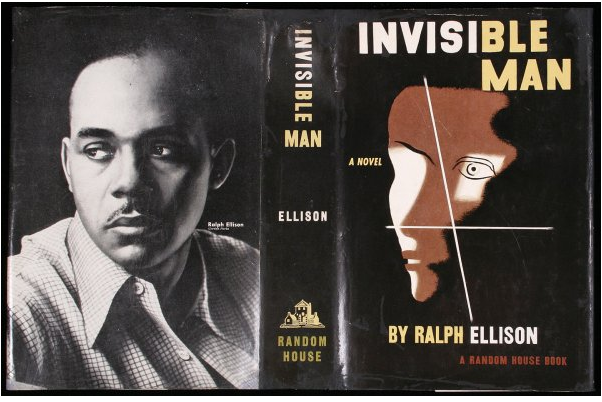

Ralph Ellison

At first I thought it was a cop and a shoeshine boy; then there was a break in the traffic and across the sun-glaring bands of trolley rails I recognized Clifton. His partner had disappeared now and Clifton had the box slung to his left shoulder with the cop moving slowly behind and to one side of him. They were coming my way, passing a newsstand, and I saw the rails in the asphalt and a fire plug at the curb and the flying birds, and thought, You’ll have to follow and pay his fine . . . just as the cop pushed him, jolting him forward and Clifton trying to keep the box from swinging against his leg and saying something over his shoulder and going forward as one of the pigeons swung down into the street and up again, leaving a feather floating white in the dazzling backlight of the sun, and I could see the cop push Clifton again, stepping solidly forward in his black shirt, his arm shooting out stiffly, sending him in a head-snapping forward stumble until he caught himself, saying something over his shoulder again, the two moving in a kind of march that I’d seen many times, but never with anyone like Clifton. And I could see the cop bark a command and lunge forward, thrusting out his arm and missing, thrown off balance as suddenly Clifton spun on his toes like a dancer and swung his right arm over and around in a short, jolting arc, his torso carrying forward and to the left in a motion that sent the box strap free as his right foot traveled forward and his left arm followed through in a floating uppercut that sent the cop’s cap sailing into the street and his feet flying, to drop him hard, rocking from left to right on the walk as Clifton kicked the box thudding aside and crouched, his left foot forward, his hands high, waiting. And between the flashing of cars I could see the cop propping himself on his elbows like a drunk trying to get his head up, shaking it and thrusting it forward — And somewhere between the dull roar of traffic and the subway vibrating underground I heard rapid explosions and saw each pigeon diving wildly as though blackjacked by the sound, and the cop sitting up straight now, and rising to his knees looking steadily at Clifton, and the pigeons plummeting swiftly into the trees, and Clifton still facing the cop and suddenly crumpling.

He fell forward on his knees, like a man saying his prayers just as a heavy-set man in a hat with a turned down brim stepped from around the newsstand and yelled a protest. I couldn’t move. The sun seemed to scream an inch above my head. Someone shouted. A few men were starting into the street. The cop was standing now and looking down at Clifton as though surprised, the gun in his hand. I took a few steps forward, walking blindly now, unthinking, yet my mind registering it all vividly. Across and starting up on the curb, and seeing Clifton up closer now, lying in the same position, on his side, a huge wetness growing on his shirt, and I couldn’t set my foot down. Cars sailed close behind me, but 1 couldn’t take the step that would raise me up to the walk. I stood there, one leg in the street and the other raised above the curb, hearing whistles screeching and looked toward the library to see two cops coming on in a lunging, big-bellied run. I looked back to Clifton, the cop was waving me away with his gun, sounding like a boy with a changing voice.

“Get back on the other side,” he said. He was the cop that I’d passed on Forty-third a few minutes before. My mouth was dry.

[Later, after this encounter, the protagonist who saw his friend get shot stands before a growing black crowd and preaches his own post-shooting wakefulness at them – jt]

“I’ve told you to go home,” I shouted, “but you keep standing there. Don’t you know it’s hot out here in the sun? So what if you wait for what little I can tell you? Can I say in twenty minutes what was building twenty-one years and ended in twenty seconds? What are you waiting for, when all I can tell you is his name? And when I tell you, what will you know that you didn’t know already, except perhaps, his name?”

“I’ve told you to go home,” I shouted, “but you keep standing there. Don’t you know it’s hot out here in the sun? So what if you wait for what little I can tell you? Can I say in twenty minutes what was building twenty-one years and ended in twenty seconds? What are you waiting for, when all I can tell you is his name? And when I tell you, what will you know that you didn’t know already, except perhaps, his name?”

They were listening intently, and as though looking not at me, but at the pattern of my voice upon the air.

“All right, you do the listening in the sun and I’ll try to tell you in the sun. Then you go home and forget it. Forget it. His name was Clifton and they shot him down. His name was Clifton and he was tall and some folks thought him handsome. And though he didn’t believe it, I think he was. His name was Clifton and his face was black and his hair was thick with tight-rolled curls — or call them naps or kinks. He’s dead, uninterested, and, except to a few young girls, it doesn’t matter . . . Have you got it? Can you see him? Think of your brother or your cousin John. His lips were thick with an upward curve at the corners. He often smiled. He had good eyes and a pair of fast hands, and he had a heart. He thought about things and he felt deeply. I won’t call him noble because what’s such a word to do with one of us? His name was Clifton, Tod Clifton, and, like any man, he was born of woman to live awhile and fall and die. So that’s his tale to the minute. His name was Clifton and for a while he lived among us and aroused a few hopes in the young manhood of man, and we who knew him loved him and he died. So why are you waiting? You’ve heard it all. Why wait for more, when all I can do is repeat it?”

They stood; they listened. They gave no sign.

“Very well, so I’ll tell you. His name was Clifton and he was young and he was a leader and when he fell there was a hole in the heel of his sock and when he stretched forward he seemed not as tall as when he stood. So he died; and we who loved him are gathered here to mourn him. It’s as simple as that and as short as that. His name was Clifton and he was black and they shot him. Isn’t that enough to tell? Isn’t it all you need to know? Isn’t that enough to appease your thirst for drama and send you home to sleep it off? Go take a drink and forget it. Or read it in The Daily News. His name was Clifton and they shot him, and I was there to see him fall. So I know it as I know it.

“Here are the facts. He was standing and he fell. He fell and he kneeled. He kneeled and he bled. He bled and he died. He tell in a heap like any man and his blood spilled out like any blood; red as any blood, wet as any blood and reflecting the sky and the buildings and birds and trees, or your face if you’d looked into its dulling mirror — and it dried in the sun as blood dries. That’s all. They spilled his blood and he bled. They cut him down and he died; the blood flowed on the walk in a pool, gleamed a while, and, after awhile, became dull then dusty, then dried. That’s the story and that’s how it ended. It’s an old story and there’s been too much blood to excite you. Besides, it’s only important when it fills the veins of a living man. Aren’t you tired of such stories? Aren’t you sick of the blood? Then why listen, why don’t you go? It’s hot out here. There’s the odor of embalming fluid. The beer is cold in the taverns, the saxophones will be mellow at the Savoy; plenty good-laughing-lies will be told in the barber shops and beauty parlors; and there’ll be sermons in two hundred churches in the cool of the evening, and plenty of laughs at the movies. Go listen to ‘Amos and Andy’ and forget it. Here you have only the same old story. There’s not even a young wife up here in red to mourn him. There’s nothing here to pity, no one to break down and shout. Nothing to give you that good old frightened feeling. The story’s too short and too simple. His name was Clifton, Tod Clifton, he was unarmed and his death was as senseless as his life was futile. He had struggled for Brotherhood on a hundred street corners and he thought it would make him more human, but he died like any dog in a road.

“All right, all right,” I called out, feeling desperate. It wasn’t the way I wanted it to go, it wasn’t political. Brother Jack probably wouldn’t approve of it at all, but I had to keep going as I could go.

“Listen to me standing up on this so-called mountain!” I shouted. “Let me tell it as it truly was! His name was Tod Clifton and he was full of illusions. He thought he was a man when he was only Tod Clifton. He was shot for a simple mistake of judgment and he bled and his blood dried and shortly the crowd trampled out the stains. It was a normal mistake of which many are guilty: He thought he was a man and that men were not meant to be pushed around. But it was hot downtown and he forgot his history, he forgot the time and the place. He lost his hold on reality. There was a cop and a waiting audience but he was Tod Clifton and cops are everywhere. The cop? What about him? He was a cop. A good citizen. But this cop had an itching finger and an eager ear for a word that rhymed with ‘trigger,’ and when Clifton fell he had found it. The Police Special spoke its lines and the rhyme was completed. Just look around you. Look at what he made, look inside you and feel his awful power. It was perfectly natural. The blood ran like blood in a comic-book killing, on a comic-book street in a comic-book town on a comic-book day in a comic-book world.

“Tod Clifton’s one with the ages. But what’s that to do with you in this heat under this veiled sun?”

— Ralph Ellison “Invisible Man”

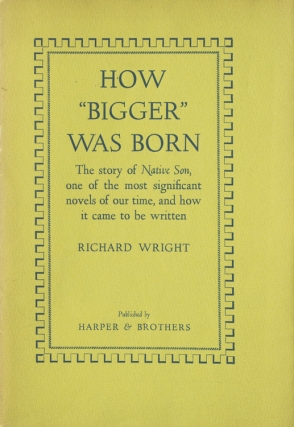

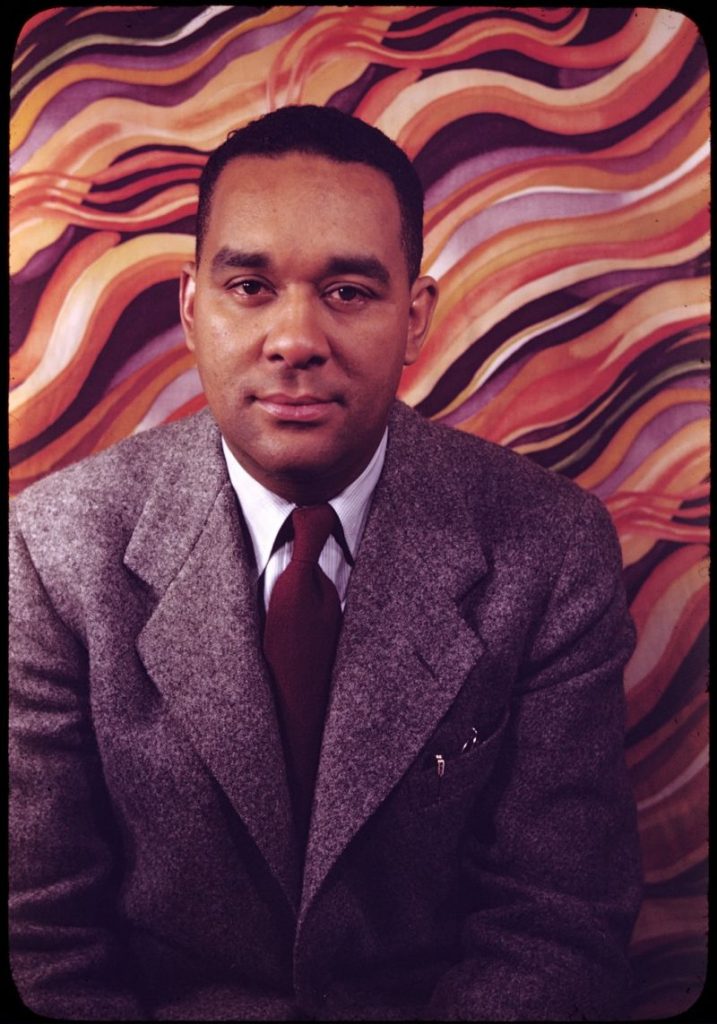

Richard Wright

Let me describe this stereotyped situation: A crime wave is sweeping a city and citizens are clamoring for police action. Squad cars cruise the Black Belt and grab the first Negro boy who seems to be unattached and homeless. He is held for perhaps a week without charge or bail, without the privilege of communicating with anyone, including his own relatives. After a few days this boy “confesses” anything that he is asked to confess, any crime that handily happens to be unsolved and on the calendar. Why does he confess? After the boy has been grilled night and day, hanged up by his thumbs, dangled by his feet out of twenty-story windows, and beaten (in places that leave no scars—cops have found a way to do that), he signs the papers before him, papers which are usually accompanied by a verbal promise to the boy that he will not go to the electric chair. Of course, he ends up by being executed or sentenced for life. If you think I’m telling tall tales, get chummy with some white cop who works in a Black Belt district and ask him for the lowdown.

When a black boy is carted off to jail in such a fashion, it is almost impossible to do anything for him. Even well-disposed Negro lawyers find it difficult to defend him, for the boy will plead guilty one day and then not guilty the next, according to the degree of pressure and persuasion that is brought to bear upon his frightened personality from one side or the other. Even the boy’s own family is scared to death; sometimes fear of police intimidation makes them hesitate to acknowledge that the boy is a blood relation of theirs.

When a black boy is carted off to jail in such a fashion, it is almost impossible to do anything for him. Even well-disposed Negro lawyers find it difficult to defend him, for the boy will plead guilty one day and then not guilty the next, according to the degree of pressure and persuasion that is brought to bear upon his frightened personality from one side or the other. Even the boy’s own family is scared to death; sometimes fear of police intimidation makes them hesitate to acknowledge that the boy is a blood relation of theirs.

Such has been America’s attitude toward these boys that if one is picked up and confronted in a police cell with ten white cops, he is intimidated almost to the point of confessing anything. So far removed are these practices from what the average American citizen encounters in his daily life that it takes a huge act of his imagination to believe that it is true; yet, this same average citizen, with his kindness, his American sportsmanship and good will, would probably act with the mob if a self-respecting Negro family moved into his apartment building to escape the Black Belt and its terrors and limitations….

— Richard Wright, “How Bigger Was Born”

All I seem to be able to say is “Jesus, dear Jesus, Jesus.”