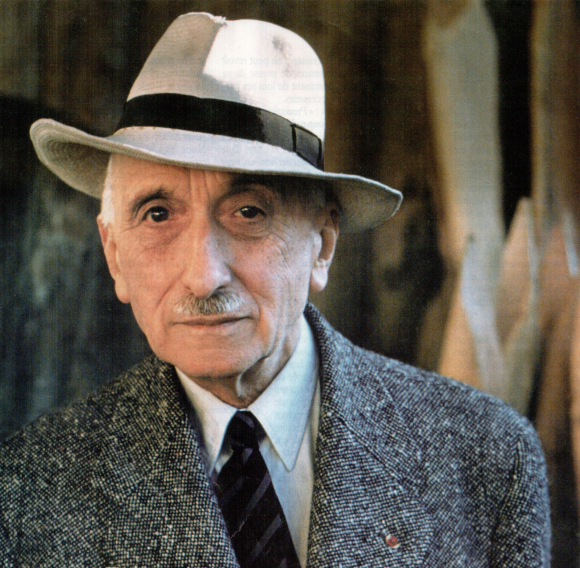

For many years, I have held a little known French author as one of the most precious treasures literature ever produced. Francois Mauriac was either a Christian with an existentialist’s heart or an Existentialist with a Christian’s heart, though that description is also misleading. He was a diarist of human suffering.

My dear late friend and mentor, Dawn Mortimer, introduced me to Mauriac’s writings decades ago. The novel a small group of us ended up reading alone but spiritedly discussing was “Viper’s Tangle” (sometimes also called “Knot of Vipers”). That novel provoked among us one of the most fascinating discussions on sin and redemption I’ve ever experienced. It is still a story I cannot think of without an intense sense of not only untangling the mystery of its protagonist, but also the mystery of myself. I have devoured sixteen-odd Mauriac novels since, five or six of them multiple times, and never come away without illumination.

My dear late friend and mentor, Dawn Mortimer, introduced me to Mauriac’s writings decades ago. The novel a small group of us ended up reading alone but spiritedly discussing was “Viper’s Tangle” (sometimes also called “Knot of Vipers”). That novel provoked among us one of the most fascinating discussions on sin and redemption I’ve ever experienced. It is still a story I cannot think of without an intense sense of not only untangling the mystery of its protagonist, but also the mystery of myself. I have devoured sixteen-odd Mauriac novels since, five or six of them multiple times, and never come away without illumination.

Mauriac’s history, as he himself admits, was for the most part extremely provincial — the same way most of his characters’ lives appear to be on the surface. It is beneath the surface where torment exists in his world. He influenced writers from Grahame Greene to Shusaku Endo. He was born in 1885 and died in 1970.

World War II had ended only half a decade before his Prize was awarded, and he had faithfully worked with the French Resistance during the war. His encounter with Elie Weisel, author of the harrowing concentration camp memoir “Night,” has been told wonderfully by both men; Mauriac wrote the introduction to “Night” and there touched on some of the same themes he does in this speech.

I once asked Larry Woiwode (“What I’m Going to Do, I Think,” “Beyond the Bedroom Wall”) about Mauriac. His response was terse. “Too sentimental,” he quipped. Perhaps I interrupted him, or someone else did, because I didn’t get to find out just what he meant. To me, sentiment is precisely not what Mauriac’s writings offer. He offers love… but at a price that many readers probably do not want to pay. My prayer is that readers in this 21st Century rediscover this literary master of the human heart.

François Mauriac’s speech at the Nobel Banquet at the City Hall in Stockholm, December 10, 1952.

Prior to the speech, Harald Cramér, Member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, addressed the French writer:

“Mr. Mauriac – In your work you have penetrated into the hearts of men, and you have shown them as you saw them: human, all too human. You did not hesitate to use the saddest and most sombre colours, if truth required it. Still, as one of your characters says, ‘One can reach the supernatural through the base’ – and if you have painted sad pictures of human life, you have also shown the rays of faith and divine grace which illuminate the darkness. Rest assured of our sincere and profound admiration.”

Then Francois Mauriac spoke:

The last subject to be touched upon by the man of letters whom you are honouring, I think, is himself and his work. But how could I turn my thoughts away from that work and that man, from those poor stories and that simple French writer, who by the grace of the Swedish Academy finds himself all of a sudden burdened and almost overwhelmed by such an excess of honour? No, I do not think that it is vanity which makes me review the long road that has led me from an obscure childhood to the place I occupy tonight in your midst.

When I began to describe it, I never imagined that this little world of the past which survives in my books, this corner of provincial France hardly known by the French themselves where I spent my school holidays, could capture the interest of foreign readers. We always believe in our uniqueness; we forget that the books which enchanted us, the novels of George Eliot or Dickens, of Tolstoy or Dostoevsky, or of Selma Lagerlöf, described countries very different from ours, human beings of another race and another religion. But nonetheless we loved them only because we recognized ourselves in them. The whole of mankind is revealed in the peasant of our birthplace, every countryside of the world in the horizon seen through the eyes of our childhood. The novelist’s gift consists precisely in his ability to reveal the universality of this narrow world into which we are born, where we have learned to love and to suffer. To many of my readers in France and abroad my world has appeared sombre. Shall I say that this has always surprised me? Mortals, because they are mortal, fear the very name of death; and those who have never loved or been loved, or have been abandoned and betrayed or have vainly pursued a being inaccessible to them without as much as a look for the creature that pursued them and which they did not love – all these are astonished and scandalized when a work of fiction describes the loneliness in the very heart of love. “Tell us pleasant things”, said the Jews to the prophet Isaiah. “Deceive us by agreeable falsehoods.”

When I began to describe it, I never imagined that this little world of the past which survives in my books, this corner of provincial France hardly known by the French themselves where I spent my school holidays, could capture the interest of foreign readers. We always believe in our uniqueness; we forget that the books which enchanted us, the novels of George Eliot or Dickens, of Tolstoy or Dostoevsky, or of Selma Lagerlöf, described countries very different from ours, human beings of another race and another religion. But nonetheless we loved them only because we recognized ourselves in them. The whole of mankind is revealed in the peasant of our birthplace, every countryside of the world in the horizon seen through the eyes of our childhood. The novelist’s gift consists precisely in his ability to reveal the universality of this narrow world into which we are born, where we have learned to love and to suffer. To many of my readers in France and abroad my world has appeared sombre. Shall I say that this has always surprised me? Mortals, because they are mortal, fear the very name of death; and those who have never loved or been loved, or have been abandoned and betrayed or have vainly pursued a being inaccessible to them without as much as a look for the creature that pursued them and which they did not love – all these are astonished and scandalized when a work of fiction describes the loneliness in the very heart of love. “Tell us pleasant things”, said the Jews to the prophet Isaiah. “Deceive us by agreeable falsehoods.”

Yes, the reader demands that we deceive him by agreeable falsehoods.

Nonetheless, those works that have survived in the memory of mankind are those that have embraced the human drama in its entirety and have not shied away from the evidence of the incurable solitude in which each of us must face his destiny until death, that final solitude, because finally we must die alone.

This is the world of a novelist without hope. This is the world into which we are led by your great Strindberg. This would have been my world were it not for that immense hope by which I have been possessed practically since I awoke to conscious life. It pierces with a ray of light the darkness that I have described. My colour is black and I am judged by that black rather than by the light that penetrates it and secretly burns there. Whenever a woman in France tries to poison her husband or to strangle her lover, people tell me: “Here is a subject for you.” They think that I keep  some sort of museum of horrors, that I specialize in monsters. And yet, my characters differ in an essential point from almost any others that live in the novels of our time: they feel that they have a soul. In this post-Nietzschean Europe where the echo of Zarathustra’s cry “God is dead” is still heard and has not yet exhausted its terrifying consequences, my characters do not perhaps all believe that God is alive, but all of them have a conscience which knows that part of their being recognizes evil and could not commit it. They know evil. They all feel dimly that they are the creatures of their deeds and have echoes in other destinies.

some sort of museum of horrors, that I specialize in monsters. And yet, my characters differ in an essential point from almost any others that live in the novels of our time: they feel that they have a soul. In this post-Nietzschean Europe where the echo of Zarathustra’s cry “God is dead” is still heard and has not yet exhausted its terrifying consequences, my characters do not perhaps all believe that God is alive, but all of them have a conscience which knows that part of their being recognizes evil and could not commit it. They know evil. They all feel dimly that they are the creatures of their deeds and have echoes in other destinies.

For my heroes, wretched as they may be, life is the experience of infinite motion, of an indefinite transcendence of themselves. A humanity which does not doubt that life has a direction and a goal cannot be a humanity in despair. The despair of modern man is born out of the absurdity of the world; his despair as well as his submission to surrogate myths: the absurd delivers man to the inhuman. When Nietzsche announced the death of God, he also announced the times we have lived through and those we shall still have to live through, in which man, emptied of his soul and hence deprived of a personal destiny, becomes a beast of burden more maltreated than a mere animal by the Nazis and by all those who today use Nazi methods. A horse, a mule, a cow has a market value, but from the human animal, procured without cost thanks to a well-organized and systematic purge, one gains nothing but profit until it perishes. No writer who keeps in the centre of his work the human creature made in the image of the Father, redeemed by the Son, and illuminated by the Spirit, can in my opinion be considered a master of despair, be his picture ever so sombre.

For his picture does remain sombre, since for him the nature of man is wounded, if not corrupted. It goes without saying that human history as told by a Christian novelist cannot be based on the idyll because he must not shy away from the mystery of evil.

But to be obsessed by evil is also to be obsessed by purity and childhood. It makes me sad that the too hasty critics and readers have not realized the place which the child occupies in my stories. A child dreams at the heart of all my books; they contain the loves of children, first kisses and first solitude, all the things that I have cherished in the music of Mozart. The serpents in my books have been noticed, but not the doves that have made their nests in more than one chapter; for in my books childhood is the lost paradise, and it introduces the mystery of evil.

But to be obsessed by evil is also to be obsessed by purity and childhood. It makes me sad that the too hasty critics and readers have not realized the place which the child occupies in my stories. A child dreams at the heart of all my books; they contain the loves of children, first kisses and first solitude, all the things that I have cherished in the music of Mozart. The serpents in my books have been noticed, but not the doves that have made their nests in more than one chapter; for in my books childhood is the lost paradise, and it introduces the mystery of evil.

The mystery of evil-there are no two ways of approaching it. We must either deny evil or we must accept it as it appears both within ourselves and without – in our individual lives, that of our passions, as well as in the history written with the blood of men by power-hungry empires. I have always believed that there is a close correspondence between individual and collective crimes, and, journalist that I am, I do nothing but decipher from day to day in the horror of political history the visible consequences of that invisible history which takes place in the obscurity of the heart. We pay dearly for the evidence that evil is evil, we who live under a sky where the smoke of crematories is still drifting. We have seen them devour under our own eyes millions of innocents, even children. And history continues in the same manner. The system of concentration camps has struck deep roots in old countries where Christ has been loved, adored, and served for centuries. We are watching with horror how that part of the world in which man is still enjoying his human rights, where the human mind remains free, is shrinking under our eyes like the “peau de chagrin” of Balzac’s novel.

Do not for a moment imagine that as a believer I pretend not to see the objections raised to belief by the presence of evil on earth. For a Christian, evil remains the most anguishing of mysteries. The man who amidst the crimes of history perseveres in his faith will stumble over the permanent scandal: the apparent uselessness of the Redemption. The well-reasone d explanations of the theologians regarding the presence of evil have never convinced me, reasonable as they may be, and precisely because they are reasonable. The answer that eludes us presupposes an order not of reason but of charity. It is an answer that is fully found in the affirmation of St. John: God is Love. Nothing is impossible to the living love, not even drawing everything to itself; and that, too, is written.

d explanations of the theologians regarding the presence of evil have never convinced me, reasonable as they may be, and precisely because they are reasonable. The answer that eludes us presupposes an order not of reason but of charity. It is an answer that is fully found in the affirmation of St. John: God is Love. Nothing is impossible to the living love, not even drawing everything to itself; and that, too, is written.

Forgive me for raising a problem that for generations has caused many commentaries, disputes, heresies, persecutions, and martyrdoms. But it is after all a novelist who is talking to you, and one whom you have preferred to all others; thus you must attach some value to what has been his inspiration. He bears witness that what he has written about in the light of his faith and hope has not contradicted the experience of those of his readers who share neither his hope nor his faith. To take another example, we see that the agnostic admirers of Graham Greene are not put off by his Christian vision. Chesterton has said that whenever something extraordinary happens in Christianity ultimately something extraordinary corresponds to it in reality. If we ponder this thought, we shall perhaps discover the reason for the mysterious accord between works of Catholic inspiration, like those of my friend Graham Greene, and the vast dechristianized public that devours his books and loves his films.

Yes, a vast dechristianized public! According to André Malraux, “the revolution today plays the role that belonged formerly to the eternal life.” But what if the myth were, precisely, the revolution? And if the eternal life were the only reality?

Whatever the answer, we shall agree on one point: that dechristianized humanity remains a crucified humanity. What worldly power will ever destroy the correlation of the cross with human suffering? Even your Strindberg, who descended into the extreme depths of the abyss from which the psalmist uttered his cry, even Strindberg himself wished that a single word be engraved upon his tomb, the word that by itself would suffice to shake and force the gates of eternity: “o crux ave spes unica.” After so much suffering even he is resting in the protection of that hope, in the shadow of that love. And it is in his name that your laureate asks you to forgive these all too personal words which perhaps have struck too grave a note. But could he do better, in exchange for the honours with which you have overwhelmed him, than to open to you not only his heart, but his soul? And because he has told you through his characters the secret of his torment, he should also introduce you tonight to the secret of his peace.

[This text taken from the Official Nobel Prize site; some textual spelling errors have been corrected, though the British spellings are retained. – WS Editors]

A hopefully complete list (via wikipedia) of Francois Mauriac’s Novels, Novellas, and short stories.

1913 – L’Enfant chargé de chaînes («Young Man in Chains», tr. 1961)

1914 – La Robe prétexte («The Stuff of Youth», tr. 1960)

1920 – La Chair et le Sang («Flesh and Blood», tr. 1954)

1921 – Préséances («Questions of Precedence», tr. 1958)

1922 – Le Baiser au lépreux («The Kiss to the Leper», tr. 1923 / «A Kiss to the Leper», tr. 1950)

1923 – Le Fleuve de feu («The River of Fire», tr. 1954)

1923 – Génitrix («Genetrix», tr. 1950)

1923 – Le Mal («The Enemy», tr. 1949)

1925 – Le Désert de l’amour («The Desert of Love», tr. 1949) (Awarded the Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française, 1926.)

1927 – Thérèse Desqueyroux («Thérèse», tr. 1928 / «Thérèse Desqueyroux», tr. 1947 and 2005)

1928 – Destins («Destinies», tr. 1929 / «Lines of Life», tr. 1957)

1929 – Trois Récits A volume of three stories: Coups de couteau, 1926; Un homme de lettres, 1926; Le Démon de la connaissance, 1928

1930 – Ce qui était perdu («Suspicion», tr. 1931 / «That Which Was Lost», tr. 1951)

1932 – Le Nœud de vipères («Vipers’ Tangle», tr. 1933 / «The Knot of Vipers», tr. 1951)

1933 – Le Mystère Frontenac («The Frontenac Mystery», tr. 1951 / «The Frontenacs», tr. 1961)

1935 – La Fin de la nuit («The End of the Night», tr. 1947)

1936 – Les Anges noirs («The Dark Angels», tr. 1951 / «The Mask of Innocence», tr. 1953)

1938 – Plongées A volume of five stories: Thérèse chez le docteur, 1933 («Thérèse and the Doctor», tr. 1947); Thérèse à l’hôtel, 1933 («Thérèse at the Hotel», tr. 1947); Le Rang; Insomnie; Conte de Noël.

1939 – Les Chemins de la mer («The Unknown Sea», tr. 1948)

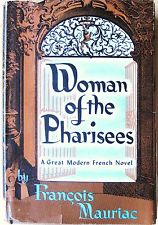

1941 – La Pharisienne («A Woman of Pharisees», tr. 1946)

1951 – Le Sagouin («The Weakling», tr. 1952 / «The Little Misery», tr. 1952) (A novella)

1952 – Galigaï («The Loved and the Unloved», tr. 1953)

1954 – L’Agneau («The Lamb», tr. 1955)

1969 – Un adolescent d’autrefois («Maltaverne», tr. 1970)

1972 – Maltaverne (the unfinished sequel to the previous novel; posthumously published)

this is amazing. thank you.