Six years ago… or was it longer?… I was asked to pinch hit with a Sunday Sermon (the JPUSA pastors were out of town or something). What I offered up was a sort of old-school “testimony,” rough-hewn and homely. Here it is, this time with photos and a few minor corrections.

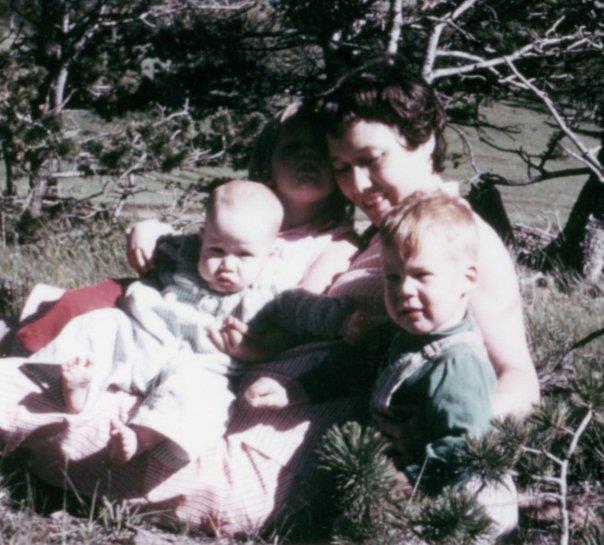

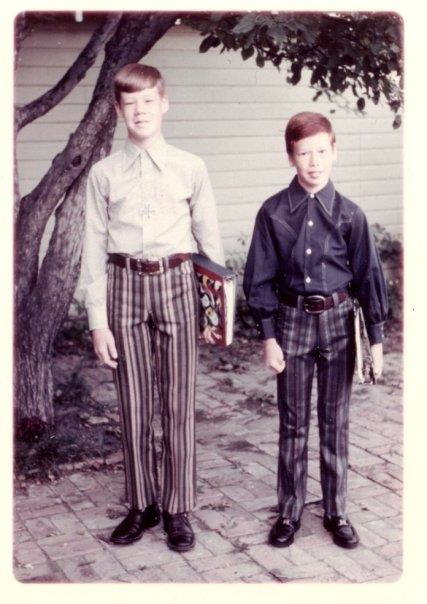

A Montana farm boy that had two very smart—and often very wise—parents, four brothers and one sister, my childhood years are mainly filled with memories of being loved, feeling certain of love.

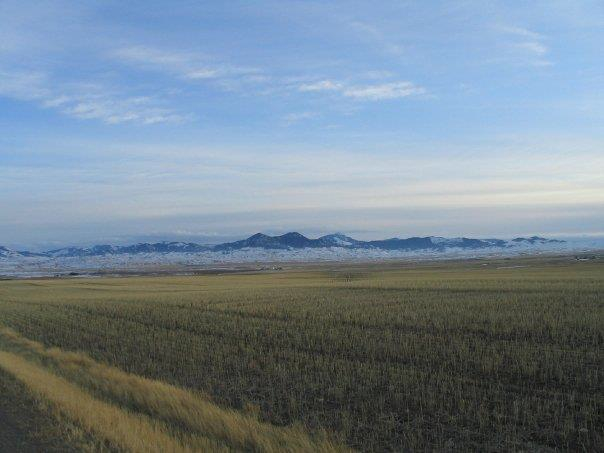

My mother cheerfully disbelieved much of the bible — especially the miraculous parts — yet had us all go to church; my dad played his beliefs about God closer to the vest. I think it was that golden childhood — surrounded by wheat fields and mountains in the summertime, and an idyllic little town called Fort Benton for the rest of the year — that laid a foundation for my deep understanding of love as the only meaning, and meaning as being rooted in love.

At a very young age I remember a magic moment, going to the doorway of our Fort Benton home and opening the door. It was a spring day, and light streamed into the living room. I was filled with an inexpressible sense of Presence, and of peace. My mother walked up behind me. “What are you doing, Jon?” I looked up at her face, which of course was love to me. “I opened the door to let God in!” My mother smiled. “And what is he wearing?” she asked. “He’s wearing a suit with purple polka-dots,” I said, without missing a beat. I guess that was the only way for a four or five year old kid to describe the indescribable.

When I was eight or nine years old, my brother Jim — eight years older than I — took me to a bible study / prayer meeting. It was part of a late 1960s revival among teenagers that took place in and around Highwood, Montana, and had swept Jim up. At the meeting a young woman spoke beautifully in tongues, and another person gave an interpretation that seemed poetic to me. I had no idea what was happening but I did sense it was something positive and gentle and about God and therefore good. I did end up in an argument with my brother on the way home about whether the bible was wholly true or not. My slam-dunk discussion-ender: “Mom and Dad don’t believe it is true and they know a lot more than you!”

But those golden childhood years were partly illusion; at some point, I was forced to realize I was both a mortal being and a moral being. A key moment was the strange incident that took place before my eyes the day Martin Luther King was assassinated (I’ve written at length about it and my loss of innocence as a result). Death and sex both became consciously real to me as I entered my twelfth year.

By thirteen, I was a haunted kid, goth before there was goth, a gloomy sort of kid that asked his friends weird questions like “Why does anything matter at all?” or “When you say you believe in God, what do you mean by the word ‘God’?” My favorite music was Black Sabbath, the Who, King Crimson, and a really blasphemous band called Methuselah, whom I’d discovered in a record store’s 99 cent bin. I was reading stuff, continually, sometimes one or even two books in a day: everything from pulp SF novels and Marvel comics to Franz Kafka, Hemingway, Steinbeck, and even Christians such as C. S. Lewis.

Lewis was good even though I was young. I got much of what he was saying in Mere Christianity quite clearly. He made Christianity intellectually respectable for me. But the first book making a deep inroad into my heart was Nicky Cruz’s Run, Baby, Run.

Lewis was good even though I was young. I got much of what he was saying in Mere Christianity quite clearly. He made Christianity intellectually respectable for me. But the first book making a deep inroad into my heart was Nicky Cruz’s Run, Baby, Run.  It had gangs, violence, sex… and an inner alienation I resonated with. These were Nicky Cruz’s realities. The Living, Present God who would care for a lonely, sinful boy such as Nicky moved me. The book was no work of art. But for me, it rang true.

It had gangs, violence, sex… and an inner alienation I resonated with. These were Nicky Cruz’s realities. The Living, Present God who would care for a lonely, sinful boy such as Nicky moved me. The book was no work of art. But for me, it rang true.

Around that time, I saw a TV special on the Jesus movement; I loved the idea of young Christians living communally and trying to be like Jesus, even though I had no idea of what being a Christian really meant. The Jesus commune in the story seemed to embody the coolest elements of the 1960s and touched on some mysterious level the yearnings of my heart. Sadly, later on the group featured in the TV special — the Children of God — was exposed as a dictatorial and sexually perverse negation of all the group’s name promised. But that original idea, a spiritual family of sorts rooted in and existing as an expression of love, captured my imagination.

I first “went forward” that same year during a Lay Witness Mission our liberal Methodist Church had mistakenly invited to come to hold services. These down-home Texans were warm, earnest Christians. I especially remember one older man who, after I’d gone forward, gently urged me to read my bible and pray often. But my father didn’t understand the whole thing; when I eagerly told him I’d become a believer, his baffled response seemed to kill something in me. I actually remember thinking an anti-prayer at the very moment: “Well. Forget it, then.” And I tried to.

One doesn’t forget God. And occasionally I’d flirt with him. Other times, I’d test him with ridiculous methods: “If you are God,” I said more than once while playing basketball alone on our driveway court, “make this ball go in.” And I’d close my eyes, fling the ball heavenward, and then open them just in time to see it bounce off the garage roof into the street. God apparently didn’t play by my rules. Other times alone in my room I’d scream at Him (quiet so my parents wouldn’t hear), “Why won’t you prove to me you exist?!” Silence.

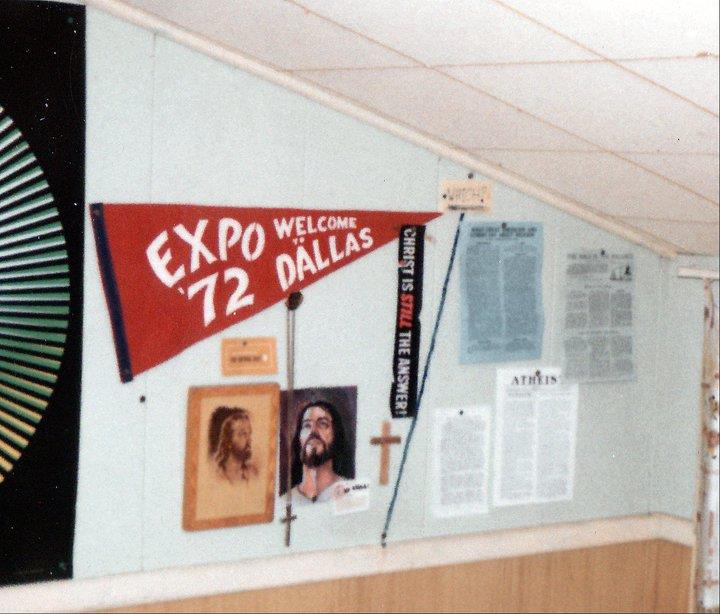

Between fourteen and fifteen, I put up a wall of stuff in my room in Fort Benton. A diagonal line of scotch tape I’d hand-colored with green marker to make it visible ran down the wall. On one side of the tape, a bunch of Christian tracts and fliers. On the other side of the tape, an array of atheist literature I’d gotten mailed to me by two groups producing such stuff. A small but highly visible hand-lettered sign posted directly over the tape’s dividing line made my anxiety clear. “Which?” That’s all it said.

But beside Christianity and atheism there were other choices. Malcolm X’s autobiography deeply impressed me, and probably radicalized me in a way I still believe was wholly good. He helped further strip away my dangerous white naivety. Because of him, I flirted briefly with Islam before discovering that Islamic cultures had themselves sometimes had slaves. And I wasn’t compelled by the Islamic story itself – Allah’s mysterious, imperious, and seemingly impersonal distance had no purchase on my imagination and no resonance of authenticity. The Muslim Jesus — Isa — was a teacher — and I didn’t need a teacher. I needed a Savior, a Lover, a Friend. I needed the all-powerful, yet completely vulnerable, God-Man.

But beside Christianity and atheism there were other choices. Malcolm X’s autobiography deeply impressed me, and probably radicalized me in a way I still believe was wholly good. He helped further strip away my dangerous white naivety. Because of him, I flirted briefly with Islam before discovering that Islamic cultures had themselves sometimes had slaves. And I wasn’t compelled by the Islamic story itself – Allah’s mysterious, imperious, and seemingly impersonal distance had no purchase on my imagination and no resonance of authenticity. The Muslim Jesus — Isa — was a teacher — and I didn’t need a teacher. I needed a Savior, a Lover, a Friend. I needed the all-powerful, yet completely vulnerable, God-Man.

I also dabbled with the westernized versions of eastern Hindu-based mysticism. They seemed rooted in a universe where “goodness” was defined only by knowledge. If you had the “inner knowledge,” you became one of the masters, one of the so-called “adepts,” maybe even a guru. What about someone starving, or being oppressed? It was their karma; they deserved what they were getting. No wonder middle-class Americans were flocking to this cotton candy theology!

I also dabbled with the westernized versions of eastern Hindu-based mysticism. They seemed rooted in a universe where “goodness” was defined only by knowledge. If you had the “inner knowledge,” you became one of the masters, one of the so-called “adepts,” maybe even a guru. What about someone starving, or being oppressed? It was their karma; they deserved what they were getting. No wonder middle-class Americans were flocking to this cotton candy theology!

But first and foremost it occurred to me that maybe all religions were merely a thin, self-deceiving veneer over the harsh reality that our lives mean nothing – nothing at all. What if we were accidents, a sort of evolutionary joke from a random and closed universe? If that was true, the best answer to my quest was in fact only a godless, meaningless pleasure, pleasure until the sadness at last overwhelmed me and the choice of exiting existence by one’s own hand would be exercised.

Yet Christ haunted me. The story rang so true, even though the story-tellers were almost always lame. Some of them were sincere, and those I respected even while – with that deadly Trott ability to judge everything into dust – I declined to live in the neat frame of their dogmatic certainty. One missionary from a local bible church threatened me with hell, glaring at me kindly through his thick glasses. “I’m not afraid of hell,” I responded truthfully, if naively. “I’m afraid of believing something that isn’t true.”

I grew up in a Methodist Church where the opposite of that missionary’s belief was preached; the historical truth of the bible was openly questioned, and even the gospel story itself was deemed untrue, or to put it more accurately, unimportant from a historical point of view. I was not a Christian, but was astonished at the pastor. We crossed swords more than once, me asking him to explain what he meant when he used the word “God” and him telling me “God means many things to many people… there are many roads to Rome.” My unfortunately snarly response: “I thought that’s what you meant. Truth is, when you say ‘God’ you don’t know what you mean!”

There was one more thing I hated about almost all varieties of American Christianity. It seemed mixed with a moralistic nationalism. Heavy emphasis on the nuclear family, American values (meaning white middle class values), and mixing sacred Christian images with images of flag and country. Martin Luther King got his head cracked by a brick in Chicago, then outright murdered in Memphis, but while growing up I never heard one word uttered from a pulpit – even our so-called “liberal” Methodist pulpit – about racism or classism in America. Where was the Jesus who said, “As you’ve done it to the least of these you have done it to me?” Their tame, white, blue-eyed American Jesus had no meaning for me.

There was one more thing I hated about almost all varieties of American Christianity. It seemed mixed with a moralistic nationalism. Heavy emphasis on the nuclear family, American values (meaning white middle class values), and mixing sacred Christian images with images of flag and country. Martin Luther King got his head cracked by a brick in Chicago, then outright murdered in Memphis, but while growing up I never heard one word uttered from a pulpit – even our so-called “liberal” Methodist pulpit – about racism or classism in America. Where was the Jesus who said, “As you’ve done it to the least of these you have done it to me?” Their tame, white, blue-eyed American Jesus had no meaning for me.

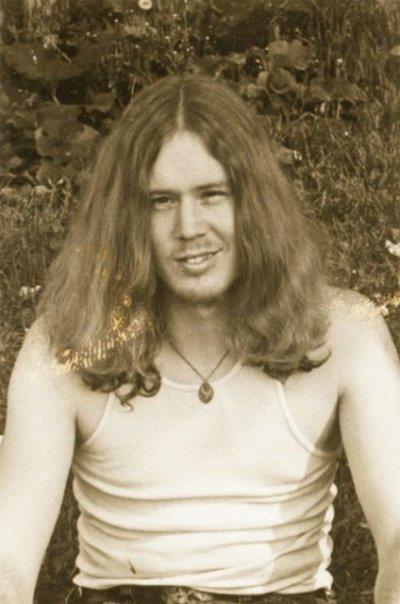

And so with all or most of this swirling in my head, teenaged angst mixed with way too much teenaged testosterone, I went to a music camp. Music – classical voice – was what I did best. And with the music I had sex with a girl and smoked dope – repeatedly – and went to a Transcendental meditation seminar and came home convinced I’d finally become “mature enough” to let go of that Jesus thing once and for all.

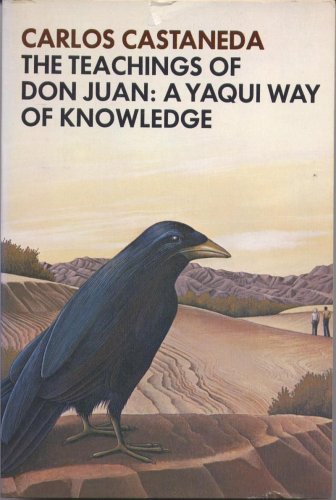

My mother confronted me. “We know about you using marijuana at that camp.” And coolly, calmly, I said to her, “Yes. And that’s not all I’ll be doing.” After all, at camp I’d been reading Carlos Castaneda’s A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, and was interested in trying hallucinogenics if I could get my hands on some.

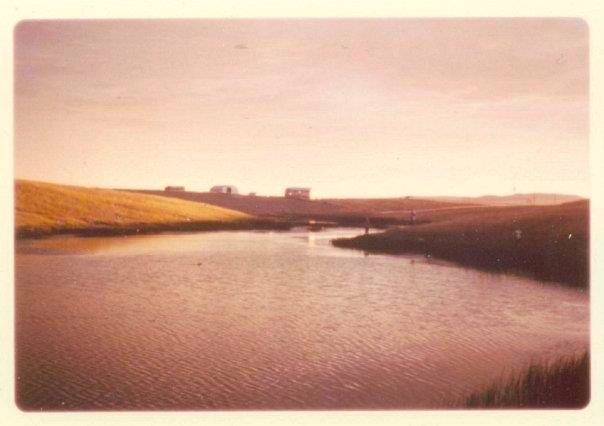

Later that afternoon I went outside our Shonkin farmhouse and sat looking off at the mountains near our farm. Blue in the distance, they could have in their mysterious immovability represented the questions still running through my head… stars, one by one, began coming out. The sky above me was clear but for a wispy cloud or two, and the slightest breeze caressed my face. I began congratulating myself on my new, gently hedonistic outlook. And then – “That was wrong what you said to your mother.” Startled, I wasted no time in praying one of the most honest prayers I’d ever prayed. “I don’t know who you are – Moses or Jesus or Billy Graham – but I’m sick of you. I’m through with you! I don’t need you anymore! Just leave.” And I absolutely meant it.

Something did leave. For a moment, it was as though I was falling into myself. There was nothing there but my self, falling inward deeper and deeper to a darkness I sensed was my own emptiness. And – this is the part you may disbelieve, which is understandable – something else happened. The sky suddenly filled with clouds – how much or little time passed I do not know – and the breeze turned into a shifting, twisting wind blowing harsh against me. I leapt up, ran into the house and down the stairs to the bedroom I shared with my four brothers. Once in bed, I tried to convince myself that what had happened was a “psychological episode” created by my subconscious. This was not successful.

The fear of God is the beginning of wisdom, and I knew now that He was real and not to be dismissed as I’d tried to do. But what did I need? Did I, like Nicky Cruz, need to be baptized in the Holy Spirit? Even to speak in tongues? Is that how I ended up kneeling on the farmhouse floor of a young Christian, Gary Huffman? On that floor, on a Tuesday or Wednesday night in mid-July, 1973, a few miles outside Highwood, Montana, I did pray desperately with this guy I barely knew. And I spoke in tongues, but that wasn’t what mattered. At that moment in history, I met Jesus. I mean, really met Jesus. I went under. I was being bathed in, flooded with, swept away in a current of absolutely powerful and irrefutable and pure and overwhelmingly real love. I met Jesus as His beloved, and He met me as my all, my story – not just a story anymore, but MY story now. He was, is, and will always be my story.

When high school ended, I chose a Christian college near Boston, only to discover to my dismay that many of my classmates there were raised evangelical and apparently were more interested in partying than Jesus.

I was alienated by this evangelical subculture, increasingly aware that I simply didn’t belong there. Where did I belong? I looked at a Cornerstone newspaper, one I’d held onto after having it handed to me as I walked through Chicago’s O’Hare airport on the way home to Montana. Cornerstone was a freaky underground looking publication by a Chicago group called Jesus People USA. I struggled with what seemed increasingly a sense of being called to go to Chicago. But joining a Christian freak commune seemed too radical, too risky. Months passed while I struggled. Finally, completely desperate, I was confronted by God: “Why should I tell you what to do, when you won’t do it?”

Stung, I repented. And I knew instantly in the most quiet and peaceful way that God wanted me at JPUSA. I joined Jesus People USA January 16, 1977. And by the time I lived with these crazy, fragile, sinful yet being redeemed people for four or five weeks, I knew I’d found my tiny place in God’s kingdom. JPUSA was a family of misfits, and I fit right in. We were wounded, broken, sinful people – still are, in case anyone forgot – but in the midst of us I once again met Jesus.

After nine or ten months doing all sort of things from moving to painting to woodstripping, I became impatient. I wanted to write for Cornerstone. Instead, I was once again conscripted to take a crew of guys out in a moving truck. Only this time we were going to the Calumet City dump, with a load of old windows and other trash removed from the community’s 4431 N. Paulina building. And all the way out there the guys in the truck were whining and fighting with each other. We got out there, dumped the truck’s contents, and I tried to straighten everyone out.

As I drove us home, I started arguing with God. “Is this it, then? Is this why you had me leave Gordon and come out here? To drive a truck?” And unmistakably in my inner heart, I heard the Lord’s direct reply. “If I asked you to drive this truck the rest of your life, would you do it?” This was God talking to me. I had to tell the truth. “Yes, Lord. If it was you asking me, how could I refuse? I’d drive this truck for you.” And rolling down I-55 a tremendous sense of peace filled me. Again, I met and trusted Jesus.

Only weeks later, I was asked to join the Cornerstone staff. Prayers answered, but also the place where Jesus did much of his deep work in my life. Cornerstone’s editor Dawn Mortimer – though she’d not met Curt yet back then – was used by the Lord to get at my passivity. That was some nasty stuff, because it masqueraded as niceness. But it was stubborn rebellion, a way of saying “no” without actually saying anything at all. And so “nice Jon” started dying, while a more real version of me slowly emerged. I learned to meet and submit to Jesus through the words of others, even words I did not want to hear as well as words that encouraged and built up.

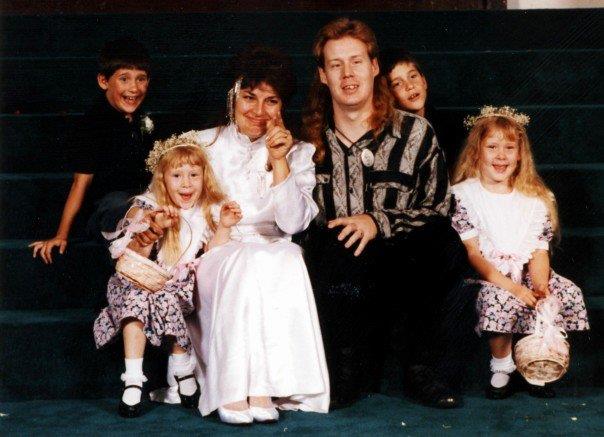

I married, and had two precious girls with my wife. But she became restless married to me and living in the community, and left me just two weeks short of our eighth anniversary. Again, Jesus met me. I found myself abandoned, alone even in the midst of the community. Without the community I’d have been far worse off. But even in community, one discovers there are times when a burden can only be partially shared. I felt a potent sense of rejection, of loss, and of fear. I once woke up to a scream – a scream I slowly realized was my own. But I began reading the Bible aloud to myself, spontaneously pausing and praying between verses. The words flowing over me were food, drink, and the embrace of my Father, Comforter, and Friend. I knew the marriage would only survive if my wife chose for it to, but I continually feared for my children. Perhaps God knew what a heart can bear, because by his grace my girls remained with me when, in June of 1988, the divorce was finalized.

I noticed a woman in the community whose husband had left her and her twin boys. Carol cheerfully lent me her entire library on marriage and divorce, just about every Christian book there was it seemed like. And as we talked over days and months, I began to see her as a fellow traveler. It became a matter of prayer. We talked both with each other and with others we respectively were close to and trusted for spiritual discernment. I watched her with my girls – Tabitha once said to her, “Can you pretend to be my mommy?” Carol doubtless watched me with her boys. And despite the fact I almost wrecked Chris’ hand by tossing him a super-pop-fly and nearly busting his thumb, she seemed to think I was alright as father material. We married, and were glad.

Jesus met me in Carol. And he meets me every morning in her and through her. For 22+ years, all I have had to do is see her and I think of Him, feel his Presence. In Proverbs 31 it talks about a woman doing a man good, not harm, all the days of her life. Well, that’s my Carol. And my love for her is so associated with my love for Him in my heart that I can no longer neatly divide them.

And that is how it is with all of you. I have lived in this community for 35 years and counting. And I see Jesus – I meet Jesus – in each of you. I pray and hope that sometimes the reverse is also true, that you meet Jesus in me. It isn’t always easy, holding on to the love that brought each of us here. It isn’t always pretty, the intersection between sanctification and sin in each of us and in all of us as we move and live together. But I meet Jesus here. I see Jesus here. Do you? I can’t imagine, for myself, being without you.

I look back to the young man who was so full of doubt, so painfully unable to see Jesus in anything. And what seems to have happened to me is that, though my physical eyes are much worse, my spiritual eyes seem to see Jesus everywhere. It is not poetry when I say that I see Jesus in every act of kindness, every pure kiss, every tear. Love is so fragile on the one hand, so easily dismissed, belittled, and rejected. Yet love is as strong as death, jealously as strong as the grave. God is jealous for me. He has torn me, and is tearing me, out of death’s grip. Sometimes it hurts. A lot. Other times it is ecstasy. But always it is through and in Jesus’ love, His Word, and His presence.

-=+=-