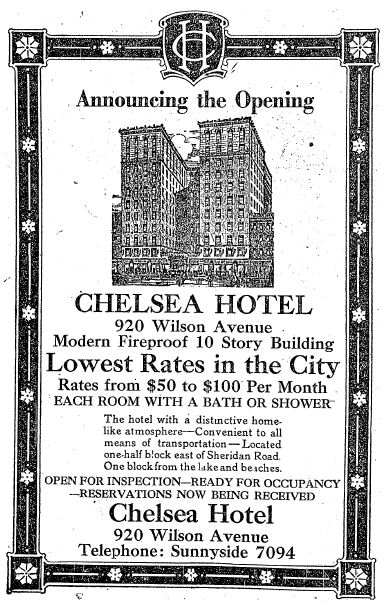

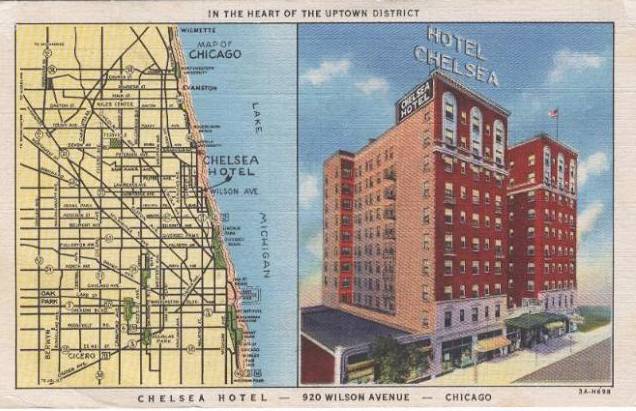

Click photo to enlarge. (From 1939-) Chelsea Hotel, – 920 Wilson Avenue, Chicago.- 356 Rooms, each with private bath and shower or shower. Located convenient to theater, churches, and the famous Wilson Ave. bathing beach, in the heart of the great Uptown District. Garage in Connection. Excellent Dining Room Service at reasonable prices.- Elevated, surface car and bus transportation, outer drive from Loop for motorists. Attractive Daily and Weekly Rates. Phone: LONgbeach 3000.

The wonderful thing about any building in the city is how quickly it serves as a place for and container of history. Jesus People USA’s current home of 920 W. Wilson — the Chelsea Hotel — is no exception to that rule.

* * *

When JPUSA (an intentional Christian community of some 350 individuals) bought the building out of receivership in 1990, the Chelsea was a shell of its former self. It would be hard today to imagine just how far the building has come from that nadir. But going back to the beginning, one finds a building that reflects Uptown Chicago’s own roller-coaster ride through the past and transformation as a sign of Uptown’s progressive future.

It’s been called the Chelsea Hotel, Hotel Chelsea, or (only since JPUSA bought it) The Friendly Towers. For this article series, we’ll be calling it for the most part the Chelsea hotel (capital ‘h’ optional since it usually wasn’t used in print).

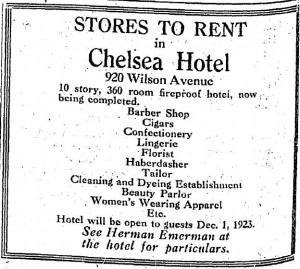

And — as with many city addresses — technically the Chelsea has more than one; old newspaper articles rarely refer to it as 918 Wilson, sometimes refer to it as 922 Wilson, and its 924 W. Wilson entrance housed a beauty shop almost since the building’s inception. (Even today the faint lettering, “Beauty Salon,” can be made out over the current Citizen Coffee & Skate Shop entrance.) It is likely 926 also belongs to Chelsea. But… We will stick with 920 W. Wilson. Whatever name or address works, the Chelsea hotel will be 90 years old in 2013.

UPTOWN: From Forests to Hotel High-Rises

To understand the history of the Chelsea Hotel, one has to understand Uptown Chicago. A full history of Uptown is beyond the scope of our modest effort here. But suffice it to say that from woods in the early 1900s, Chicago’s “far” north lakefront area boomed in the 1920s. One of the most striking peculiarities of Uptown — one which had tremendous social significance up to the present day — was the construction of various multi-story apartment buildings in and around Wilson Avenue near Lake Michigan.

One early writer on Uptown’s changes described things thusly:

“But the character of the far North Side is distinct. It is a region of the apartment-dweller. One who explores it will find rather a surprising number of the good-natured, somewhat worn wooden dwellings of the village days; he will discover stone houses of some pretensions; he will espy many a vacant lot which, for all one can tell, may be a goodly trysting-place. But, in most parts of that region, the ‘improvements’ of the modern age have consisted chiefly of buildings in which many families live together comfortably or restlessly, friends or strangers.” [Down the Shore to Uptown, Henry Justin Smith, 1931]

The largest and longest-lasting of these buildings were hotels — hotels built for high-class clientele but which would one day provide the basis for an area of astonishing poverty vs. wealth, along with a racial and ethnic diversity unequaled anywhere else in Chicago. But we get ahead of ourselves. During the 1920s and 30s formative phase of Uptown’s history, it (like much of Chicago) was governed by strict racial quotas enforced via zoning laws.

A short version of the Chelsea Hotel’s pedigree offered by Chicago Urban History notes the hotel’s genesis during the Jazz Age — an age who’s architectural influence over Uptown cannot be over-estimated:

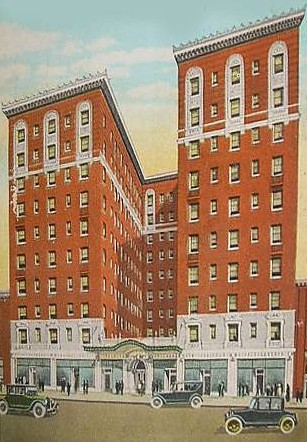

Uptown’s Hotel Chelsea, located at 920 West Wilson Avenue, was built in 1923. It was designed by architect B. Leo Steif and cost an estimated $2 million to construct. The ten-story hotel consisted of 360 single rooms, each with a private bath. According to the Chicago Tribune, the hotel’s first residents were required to rent rooms on a monthly basis in order to exclude what the newspaper called “transients.” Room rates ranged from $50 to $75 per month. During its early years, the hotel served as a meeting place for several notable community organizations, including the Uptown Optimists, the North Shore Kiwanis Club, and the influential Uptown Central Association of business leaders.

Indeed, the Kiwanis Club, according to the Chicago Daily Tribune, met weekly at the Chelsea as of December 1928. The Chelsea hotel’s rise coincided with the general boom in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood.

To again cite Chicago Urban History’s excellent article:

With the installation of new transportation facilities and the opening of the Wilson and Clarendon Avenue beaches for recreational purposes, Uptown became an increasingly attractive place to live during the 1910s and 1920s. As the demand for housing in the district grew, land values and property taxes pushed upward. Seeing both new burdens and new opportunities in the district’s shifting economic fortunes, many property owners sold their homes to developers who replaced them with larger, more profitable apartment buildings, office buildings, or movie theaters. During the 1920s, several new eight- and twelve-story apartment hotels were built on land formerly occupied by handsome mansions. The largest and most luxurious of these new apartment buildings were the Somerset (1920), Sheridan Plaza (1920), Chelsea (1923), and Lawrence Hotels (1928). Sheridan Road, once lined by mansions with spacious lawns, began to remind some observers of the Loop or upper Manhattan as the new towers rose. Elsewhere in the district, dozens of other mansions were subdivided into multi-unit rooming houses.

The “el”evated trains ran from Chicago’s downtown el “loop” to Wilson Avenue’s Uptown Station, only three short blocks from 920 Wilson’s front door. Bus lines ran to the corner of Wilson and Sheridan, a half-block from the Chelsea’s doors, as this 1922 blurb from a private motor bus company noted: “Operations of the Chicago Motor Bus Company, begun in March, 1917, and continued to date, have undoubtedly contributed materially to the rapid growth and development of uptown Chicago, the Wilson Avenue district on the North Side, and the intervening territory served…. [bus route loops] are turned back at the Edgewater Beach Hotel, 7.9 miles; at Wilson Avenue and Clark Street, 7.6 miles; and at Wilson and Sheridan, 7 miles…. The rate of fare from the beginning has been 10 cents flat.”

The night life of the area, fueled perhaps by Prohibition, was booming. Illegal taverns, barely hidden from plain view, were everywhere including across the street from 920 W. Wilson. (In fact, some fifty plus years later the Jesus People would own and “repurpose” a quite infamous former tavern and strip joint across the street… but that’s another Uptown History story for another day.) Two very well known night spots, the Via Lago (“by the lake”) and Honolulu Harry’s, were on Wilson Avenue less than one block east of the Chelsea hotel’s entrance; neither of them would survive through the twentieth century.

Another club two blocks west of the Chelsea, the Green Mill on Broadway just north of Wilson, was an Al Capone joint and still exists today (and has appeared in various movies, even being the subject of one, 1957′s “The Joker is Wild”). In 1928 Treasury Department agent Frank Wilson moved into the Sheridan Plaza, next door to the Chelsea, as part of his eventual research into and take-down of Capone via income tax fraud charges. Gangster John Dillinger in 1934 had an apartment at 4310 N. Clarendon Avenue within a few blocks of the Chelsea. And when his violent life ended that same year in a splatter of gunfire behind Chicago’s Biograph Theater, his body was taken to the McCready Funeral Home at 4506 Sheridan — one and a half blocks around the corner from the Chelsea hotel.

Uptown’s reputation as a booming night spot and wealthy area declined with Wall Street’s fortunes. None of Uptown’s nearly dozen neighboring posh hotels — from the Sheridan Plaza next door to the Grasmere just around the corner — would survive as posh. As the area’s luster faded, the large buildings were bought and sold numerous times to various speculators. The Chicago Tribune Dec 11 1935 (“Reorganize Five Former Strauss Realty Issues”) recorded that the Chelsea at 920 W. Wilson, along with four other properties in Chicago (including the Leland Hotel in Uptown), was sold as a part of an attempt to recoup mortage securities costs.

The Chelsea Takes a Dive: Crimes, Criminals, and Victims

Apparently the clientele of the Chelsea House had its criminal elements, and what would any Chicago history be without crimes stories?

One man attempted suicide at the door of a woman spurning his love,then robbed another of some shawls which he had in his Chelsea apartment when visited by a cop after him on an unrelated charge. Oops. Caught. A 1930 newspaper article chronicled a desperate 920W. Wilson resident, Walter French, attempting to rob a bank by threatening to throw nitroglycerin onto the bank floor; the small box he was carrying turned out to be fake. [Chicago Daily Tribune, Sept. 3, 1930, p.3.] Two residents of the Chelsea were arrested after robbing a taxi driver less than a block from 920′s front door at Wilson and Hazel; the duo’s take was six bucks. [Chicago Daily Tribune, November 13, 1930, p. 6.]

A gang of six men, known as the “Country Club Bandits” for their habit of knocking off (you guessed it) country clubs, met the end of many criminals. “With the arrest of Frank Chimento, 19 years old, and Rocco Prano, 18, at the Chelsea hotel, 920 Wilson avenue, yesterday morning the roundup of the gang was virtually completed.” [Chicago Daily Tribune, “Six Held as Country Club Bandits,” August 23, 1935, p. 9].

July 18, 1938′s Tribune offered a story involving three men from the Chelsea; two suspected assailants and one their shooting victim — a rug salesman named Edward Tager who’d been shot “under the heart” right in front of 920 W. Wilson. He apparently survived. [“Shot Down in Street,” Chicago Daily Tribune, p. 1.] The same worthy newspaper reported in 1938 how 920 Wilson resident and orchestra leader Johnny Maitland had been charged with being in arrears to his wife, Alice. Why this was newsworthy? Perhaps because Mrs. Maitland was a model — a fact offered not only in the news item’s text but also with a lovely photo taking up two thirds of the column. [Chicago Daily Tribune, “After Arrears,” Dec. 23, 1938, p. 12.]

“Handbook” operations at the Chelsea being disrupted by the police is a theme repeated. The cops sometimes didn’t seem all that effective: “63 Bookies Walk into Court; 63 Walk Out Again” proclaimed a Tribune article dated October 18, 1938 (p.3). The police seemed to have neglected having a warrant. “But State Attorney Courtney’s campaign against handbooks continued. His axe raiders visited and wrecked eight handbooks the afternoon, bringing the total to date to 427.” Among the eight addresses? Chelsea hotel’s seldom-used 918 Wilson address.

A black market meat scam involving the robbing of trucks run by four men and a young female nightclub singer was derailed by the cops; the singer’s boyfriend (one of the thieves) lived at 920 Wilson. [“Arraign Girl, 21, Four Men Today in Truck Looting, Tribune, July 10, 1945, p. 14.] By the late 1940s another model had been robbed of her jewels and fur coat while living at the Chelsea hotel, and in Dec. 1953 a musician and his wife, Norman and Phyllis Smith, were busted for hard drug possession, needles included, in their Chelsea digs. Lionel Jamison’s April 1953 plunge from the eighth floor of the Chelsea apparently stayed a mystery.

The July 4, 1956 Chicago Daily Tribune reported the strange case of private detective Lyle de Talent, a man involved in a court case and who was stabbed during it (June 24), but survived that only to end up dead — apparently at his own hand via a half-bottle of sleeping pills — in his Chelsea Hotel apartment. Did he commit suicide because his work, which likely led to his stabbing by assailants unknown, also led to the accused getting off due to that very work de Talent had done? Wiretapping it was, and ruled unlawful by the court. The article did not offer further enlightenment, and the death was ruled a suicide.

But the next day the paper, again noting the 920 W. Wilson address of his demise, informed its readers de Talent’s death was being investigated further after all and that 21 days were being taken to complete the examination. Alas, its readers and we are left dangling… no further follow ups were written.

One Morris Goldman became part of the Chelsea hotel’s mid-century lore; his obituary on August 17, 2001 (Chicago Tribune) noted:

“Morris ‘Maish’ Goldman, 93, a longtime Chicago tavern owner who claimed to have won his first bar in a poker game, died Tuesday, Aug. 14, in Chicago. Mr. Goldman owned the Windup and Chelsea Lounge at the Chelsea Hotel on Wilson Avenue–known in the early 1950s as a bookie joint and later as a ‘retirement hotel.’”

Goldman’s story, along with the afore-mentioned 1938 article about an afternoon raid at the Chelsea, indicate just how long-lasting the book-making activities at Chelsea were. Other Tribune articles regarding arrests of book-making outfits seem to regularly include as a residence of those arrested the 920 W. Wilson Chelsea hotel address,, underscoring Goldman’s suggestion that the place was known for such activities.

A petty and somewhat humorous crime, or perhaps a few crimes lending one another additional charm, occurred June 14 1960 when two men were apprehended at the Chelsea hotel for “tampering with a phone” there. Apparently the duo with the poetically well-suited names of Kenneth Morris and George Norris were not only involved in placing long-distance bets on horse races over the phone but also had a rig — a coin tied to some fishing line — for retrieving their money from the pay phone once it had been used. A detective — the hotel’s own dick? — nabbed ‘em in the act.

Speaking of Goldman’s Chelsea Tavern, the only mention found to date of such a place in print other than his obituary involves (of course) another crime. The June 1963 Chicago Tribune recorded — and this is the item in toto — “Herman Gale, 6540 N. Damen av., reported to police his wrist watch was stolen at a tavern at 922 W. Wilson av” (p. 12). The tavern isn’t named, but we’ll suppose it to be The Chelsea Lounge until otherwise advised by facts. The one confusing fact — one probably of no interest except to the historically obsessed — is that the Chelsea Lounge in the photo included above is on the wrong side of the building to be 922 W. Wilson… technically at least it would be 918 or even 916. The way addresses are parsed out in real life may not mirror the order one would hope for.

Innovation and Renovation

But local color aside, the Chelsea hotel was a building in disrepair and decay. The building was on its last legs. And then, in 1967, an innovative businessman had a big idea.

Part Two–> Posted as of May 16 2012!!

I would like to thank Joanne Asala of Compass Rose Horizons for her selfless help in obtaining some of the IDOT photos included in this history. Her Uptown history pages are wonderful.

My mother worked in the diner of the Chelsea hotel back in the 50s. Remember climbing around near the operator switchboard and and breaking my wrist. Also the midget wrestlers that were my size. I was 3 to 5 yrs old. We lived around the corner on Hazel

I grew up in the sixties at Hazel and Wilson and have seen alot , but I am glad to see the building being taken care of and hopefully another blessed hundred years , peace

Hello, I’m interested in getting a higher resolution version of one of the photos on this page. I’m specifically looking for the photo with the sign for Sieben’s beer. I’m researching the business that’s pictured (the Shamrock Tavern)

That’s about all I have. I got that digitally… from an Illinois IDOT website. I don’t even remember how! (eye roll at self)

My uncle Fred passed 30 some years ago and one of the things he left me was his stock certificate to the Chelsea Hotel company one share issued August 18, 1936. I wonder if it still has any value.

Jeff, is there any way you can photograph it? I’d love to add that to the history. I’d suspect that since the company itself probably went caput once the hotel was sold the first time, it probably isn’t. If you don’t want it anymore, I’d love to add it to my files.

Hello…looking for my moms history..her name was eva drew and she stayed at the Chelsea during 1944 in room 1021 that we know of for sure..that’s all we have..its a mystery for us…any way I could find out anything more?

That is way before we moved in here and unfortunately all the records of that era are long gone (the previous owners, as the articles record, renovated the place into a Seniors Home and likely any of the previous tenant records were lost). If you ever encounter photos of her here I’d love to see them. If I (very unlikely but who knows?) encounter any files from that era I will look for her name.