[This article, with a photo gallery at article’s end, is part II of a Planned III part series; Part I deals with Chelsea Hotel’s construction in the 1920s and what happened next.]

Through the 1930s into the first two-thirds of the 1960s Chelsea Hotel, despite its small studio apartments, was not just home to single adults but entire families. One former resident we recently interviewed [1] recalled his own family living at Chelsea from the mid 1950s through the purchase of the building in 1967 by developers. “The first floor was far more opened up than it is now,” he recalls. “Us kids came down here and wandered around like it was a playground.” He remembered the front of the building housing a tailor’s shop (926), beauty salon (924), barber shop (922), the Mars Delicatessen (918), and the Chelsea Lounge (916). “I had a photo of my mother and I standing right in the front entrance,” he says, pointing up at the 920 Wilson archway as we stand together outside. “I was this high.” His hand hovers only three feet from the pavement. “But we were happy. Good memories.”

I ask him what happened to the photo. “I threw it… all of our photos… away when my Mother went into a nursing home.” He tears up, explaining how the pictures only meant something when she was there to go through the album with him. I realize my historian’s dismay over destroying the photos has encountered another rationale no less compelling… at least to the person holding it.

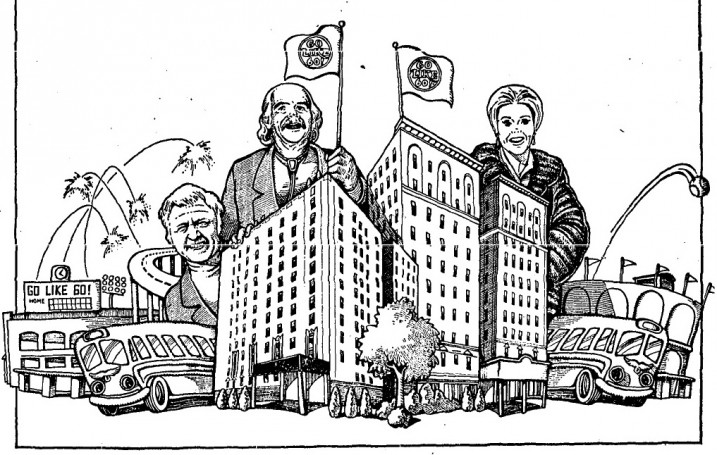

RETIREMENT HOTEL: Chicago’s First, Nation’s Largest

As detailed in Part One, the Chelsea Hotel came into existence during the economic boom of the 1920s, and there was nowhere where the 20s life was more garish than Uptown, Chicago. But then came the depression, and though it eventually would pass for most of Chicago, Uptown became the North Side’s major ghetto area. This of course influenced property values. The Chelsea Hotel was built in 1923 for $2 million, yet the Chicago Tribune reported its purchase for only $400,000 by one Leonard Richman, president of Investors Realty and Management Corporation. Richman did turn around and sink $1,125,000 more into Chelsea via an extensive renovation. The Chicago Defender (see photo below) covered the June 29, 1967 ribbon cutting ceremony: “County Board President Richard Ogilvie with numerous civic and governmental dignitaries looking on, cut the ribbon dedicating The Chelsea House, Chicago’s first privately-sponsored retirement hotel and the nation’s largest.” (Side note: Ogilvie only two years later was elected Governor of Illinois.)

Richman had one thing in mind, a then-innovative idea which would catch on like wildfire among housing providers. Richman saw in the Chelsea the perfect vehicle for a new approach to older renters with limited incomes. He turned the Chelsea House “into a senior citizens’ center, with service including three meals a day and even an in-house library. The idea was to provide acceptable living accommodations.” In November of 1967 the Chicago Housing Authority used Chelsea House as a testing ground for their “experimental” plan to rent public housing from private providers. Twenty five furnished rooms were leased to elderly individuals and couples. The marriage of low-income housing and private development seemed at that moment the best of all worlds, and it did in fact work. The seniors paid a lower rent of $37.50 while the government made up the difference of between $55 and $75 “market rental” rates. One million dollars per year was provided by the federal government for the program.

Richman had one thing in mind, a then-innovative idea which would catch on like wildfire among housing providers. Richman saw in the Chelsea the perfect vehicle for a new approach to older renters with limited incomes. He turned the Chelsea House “into a senior citizens’ center, with service including three meals a day and even an in-house library. The idea was to provide acceptable living accommodations.” In November of 1967 the Chicago Housing Authority used Chelsea House as a testing ground for their “experimental” plan to rent public housing from private providers. Twenty five furnished rooms were leased to elderly individuals and couples. The marriage of low-income housing and private development seemed at that moment the best of all worlds, and it did in fact work. The seniors paid a lower rent of $37.50 while the government made up the difference of between $55 and $75 “market rental” rates. One million dollars per year was provided by the federal government for the program.

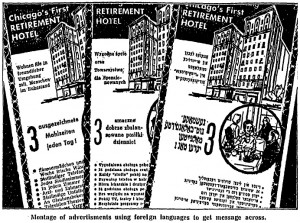

Richman’s focused-on-seniors idea was ahead of its time. And he pressed his advantage by aggressively advertising with multi-lingual ads targeting various senior populations (see photo, below). And he was quite earnest in his attempts to make these new senior citizens’ communities-within-a-single-building places where they could thrive. Not only were meals provided, but so was entertainment.

And that entertainment was often top-shelf. Stars that would appeal to seniors often showed up at 920 W. Wilson to meet and greet Chelsea House residents. They were also recruited for that aggressive ad campaign, one which experimented with a “column” and also the slogan “Go like 60!” Old Chicago Bears players, Jimmy Durante, Shirley Jones, Zsa-Zsa Gabor, Will Geer (Grampa Walton on “The Waltons”), Caesar Romero, and others represented sports and entertainment.

The Chelsea House was featured in Multi-Ethnic ads targeting German, Polish, and Jewish elderly to name a few. (Photo from 15 Dec 1967 Chicago Tribune)

The political world also sought out the residents at Chelsea House. Perhaps predictably, Mayor Daley made the rounds as did his son Richie. Da Mayor toured even Chelsea’s basement as well as kissing a blarney stone. Adlai Stevenson III, who served Illinois as a Senator and ran — twice unsuccessfully — for Governor, made sure to stop by. Republicans stopped in as well, including Elizabeth Dole when her husband made a run for the Vice-Presidency (he shared the ticket w/ Gerald Ford) in 1976 (Chicago Tribune Oct 31, p. 16). Perhaps more significant historically, at least for political junkies, was the visit of Jane Muskie to Chelsea House just days after her husband had broken into tears defending his wife from Nixonian smears. The Tribune (March 5, 1972, p. 6) noted her spirited defense of Muskie’s campaign: “The question is, do you want a man in charge of this country who is a human being, or one who never allows emotion to enter in?”

Through the 1970s, Uptown overall experienced a rash of fires. A local progressive magazine, Keep Strong, with a crusading editor who would later become alderman of the 46th Ward with Uptown at its heart, revealed that many of the fires were “Arson for Prophet.” National television news took up the story. Yet Chelsea House was contrasted with nearby buildings where fires took the lives of some while rendering others homeless. As late as the early 1980s, Chelsea was known as a quality exception to the low-cost housing rule.

LAWSUITS and BROKEN BOILERS

Unfortunately, by 1985, Chelsea House had changed hands and had begun a half-decade-long descent into misery. The city of Chicago in 1985 sued the building’s owner, H&R Realty and Ray Carlton, for negligence. The case dragged on for four more years and even into 1990. Chelsea’s clientele went from full occupancy (356 rooms) to only 185 by the end of 1989 (Chicago Tribune Dec 28, 1989, “Judge Rips City Over Housing Case”). Even employees were fined by the courts, one losing over $300 (though H&R Realty promised to repay her); in the court hearing, the complaints against the owners were specific: “City health inspectors in September cited the facility for “heavy roach infestation,“ “no running hot water,“ and “outdated meats,“ according to court records. Health officials suspended the hotel`s kitchen license for noncompliance, but reissued it two days later, after a follow-up inspection” (Chicago Tribune, Nov 2, 1989, “Retirement Hotel Aide Pleads Guilty”). The Trib also reported on a late 1989 meeting that was chilly both metaphorically and literally:

Landlord Plays It Cool, Then Feels Judge`s Heat

December 16, 1989|By George Papajohn.

The judge wore a mink coat. The lawyers from the Chicago corporation counsel`s office were bundled in overcoats. One kept her gloves on.

Ray Carlton, the owner of the building, the Chelsea House, 920 W. Wilson Ave., and his lawyer were the only ones who claimed to be unfazed by the chill in the air Friday.

The coldest day of this winter season was not a good day to be the owner of a building in court for, among other things, not providing sufficient heat. Especially when the building`s frigid cafeteria was being used as the courtroom and the boiler was on the fritz.

The elderly residents of the Chelsea, wrapped up in sweaters, coats and mufflers, peered through the glass doors of the cafeteria as temperatures outside slowly crept out of single digits and a westerly wind whipped up an arctic chill.

Associate Circuit Court Judge Consuelo Bedoya County had toured the building with city inspectors as part of a case that she said involves violations dating back to 1985. Then she held court at a lunch table.

Carlton, owner of H&R Properties, which also is in federal Bankruptcy Court, testified that he wasn`t really cold.

“I`m insulated,“ he said, his sleeves rolled up. “To a senior citizen, 75 degrees in the middle of August is cold. I can assure you that residents wear overcoats in the middle of August.“

Bedoya told Carlton that she was disappointed he had not been able to remedy heating problems discussed in court in October. She then placed the building in receivership, which means the city will be responsible for trying to fix the cantankerous boiler in the basement.

The city must now, however, go to federal court to see if a stay can be lifted on income from the property to allow the city to pay for the repairs.

That action may come Monday, by which time temperatures may actually break into the 20s. On Tuesday, Carlton is to appear before Bedoya again-this time in the relatively balmy environs of the Daley Center. [….]

In the lobby of the once-stylish Uptown building, Carl Winther, 78, was wearing a light jacket over three layers of clothing. “It`s the only way you keep warm,“ he said. “When you`re old, you don`t have the strength. When you`re young, you can fight it better.“

“About half the time, they don`t have any heat and no hot water,“ said a resident named Mike, age 86, also clad in a coat. He said that his $650-a-month room was warm but that an electric space heater deserved some of the credit.

Carlton said his sympathies lay with the residents, and that if a court-appointed receiver can get the building`s problems resolved he`s all for it. “I think it`s great,“ he said. “These people have provided me with a living for a long time. I`m friends with them.“

More on that and on the building’s transition into the home of Jesus People USA, in part III; Part I offers Chelsea Hotel’s early history and more photos.

Below is a photographic montage from Chelsea House’s archives (mouse over each photo for a short explanation of its contents):

-=-

[1] The former Chelsea resident lives today in what I feel to be a fragile social situation; for that reason he will not be identified.

( <–For Part One of “Chelsea Hotel Before the Jesus People”)

(For Part Three of “Chelsea Hotel Before the Jesus People” –> UPCOMING in 2012)

The Chelsea was the center for working musicians in Chicago for years before It became a retirement home. In the 40’s there were hundreds of working musicians living within a few blocks and the Warm Friends bar in the Chelsea was where musicians gathered by the dozens to book jobs locally and with traveling bands.

It was as well home to many stagehands at Loop theatres,tv wrestlers ,cab drivers and all manner of marginal people. It was a very good place and some people lived there for years.I lived there off & on in 1948 & 1949/50.