This article was originally published April 4, 2008.

This article was originally published April 4, 2008.

Forty years ago today, I was four days short of my eleventh birthday, a young boy in an unusually loving family growing up in Fort Benton, Montana. Fort Benton was a beautiful tiny microcosm of rugged individualism and American middle-class values. It was also virtually an all-white town, as were most towns in Montana then.

The day I remember was cool but not coat weather; I stood in our front yard near a Box Elder tree, shading my eyes against the sunlight. My child heart knew perfection.

I stood, at that moment, in the heart of the American dream. Everything around me had meaning, and all that meaning was good. It was Springtime, the fresh scent of pollen and mown lawns in the air. There was peace, order, tranquility, the quiet morning streets and bright houses mirroring back to me my own place in things. The bright sky spoke of a God who Loved me, loved me by default because I was me and existed in this throbbing good heart of my family, my town, my country.

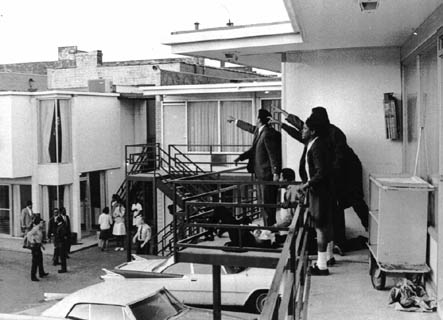

And then I heard a door slam open, saw a man — our neighbor — run into his side yard. “They got him!” he screamed, hands upraised in obvious joy. “They shot that commie nigger Martin Luther King!”

My eyes took in this event, trying to understand it. Who was he talking to? He didn’t even glance at me, it was as though he were in his own rapturous world. I stood, still as a deer in the woods, while he slowed his dance and then re-entered his home.

This was not a thing I could categorize. Why would Mr. Corman* be glad that someone had been shot? I was not shocked; I was puzzled. This was an odd event, I decided, and needed decoding.

I had heard of Dr. Martin Luther King, and I had picked up from my mother that she thought he was a good man, but a bit too extreme, perhaps even being used by forces less naive than he was. And I again went to her to discuss what I had seen. I do not remember what she said about Mr. Corman. I remember, though vaguely, her saying that what had happened was sad and wrong.

I felt nothing, but replayed over and over in my mind’s eye the leaping, springing body of our neighbor, his mouth shrieking in joy. “They got him!” and “commie nigger” and the dance of ecstasy.

There was no sorrow for me then, only curiosity. I did not actually weep over this incident until over two decades later, while recounting it in a church service.

That day I was a child, on the verge of awakening to sex, death, and all the deep things that torment and break a human heart. And when I remember that day, April 4, 1968, I remember it as the day when I had my innocence taken away, the dangerous innocence of a child raised in a nation that denies its own tortured past and present.

I mourn the child, and mourn the racial hate and ignorance that wounded him that day. I mourn the man who was both purveyor and victim of his own hatred. And I mourn the man who, even in his death, started me on a journey into the complexities, horrors, and suffering of encountering the wounds and sins of America. Sins, I slowly discovered, that I shared in, benefited from, and helped maintain by my unexamined assumptions.

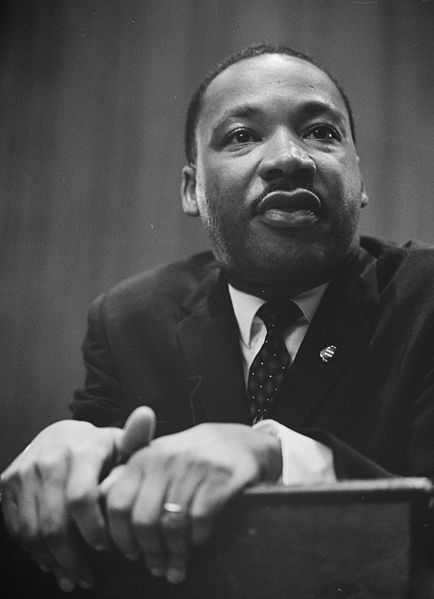

Today I honor Martin Luther King in my own heart not primarily for what he did for the nation or for black people or even for white people. I honor him for taking away my innocence and for becoming the catalyst of a quest that led me back in history and forward toward belief in a meaning beyond the American dream, which I discovered was terribly deficient at its heart. I discovered Christianity, and through King and others like him, also discovered (and am still discovering) how to untwine Christian belief from American mythology.

My innocence I began to lose that April day had been based upon the idea that America was God’s Chosen Nation, and that God loved America by default and smiled upon the choices made by our leaders. All I had to do, I thought as a child, was to embrace the goodness of the world I had been gifted.

My innocence I began to lose that April day had been based upon the idea that America was God’s Chosen Nation, and that God loved America by default and smiled upon the choices made by our leaders. All I had to do, I thought as a child, was to embrace the goodness of the world I had been gifted.

What I had not realized was that my white skin, my gender, even the language I happened to speak, served as tickets for me while simultaneously excluding Americans who did not have these characteristics. I had never seriously thought of race until that day; I did not have to think of it, because I was its beneficiary.

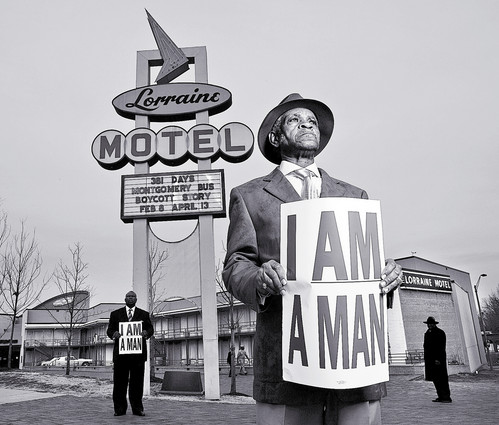

Today, I realize we all think about race. But I am less sure we really understand our racial history. To understand it, we need to study our history together, and for white people in particular it will break our hearts.

I personally do not believe that any white person can say they are free of racial naivety. I do not think I am free of it, after all these years and all the reading, praying, thinking, dialogging I have done.

I have wept over what happened that day, wept for the child I was and for the dreamer whose love was snuffed out in a moment. You see, I thought as a child that love was what we all wanted and that the world was a good, safe place. But what I learned that day was that love and suffering are bound together, while hate is always with us, always working its poisonous way, and always finding a way to destroy love’s messengers. Though not love itself…

The Christian message is that love rises up again, just as it literally — literally being very important! — rose from the grave on that first Easter. Martin Luther King was a man, a suffering, imperfect, but called out by love man. He paid the price for daring to love a world which did not want to be confronted by love.

The Christian message is that love rises up again, just as it literally — literally being very important! — rose from the grave on that first Easter. Martin Luther King was a man, a suffering, imperfect, but called out by love man. He paid the price for daring to love a world which did not want to be confronted by love.

And I, the 10 year old going on 11, did not want to be confronted by the cost of love. I wanted love but did not comprehend the truth about love. A child that young could not have been expected to carry such a burden; it would have crushed me. (Yet thousands of black children had that burden forced upon them from the day of their birth! Think on that!) That day, I learned the truth. Each day, I must choose again whether or not I will embrace the cross of truth and do my tiny tasks on its behalf.

I most likely will never be used by God as Dr. King was. I will almost certainly not be shot because I loved. But I was injured that day, forty years ago. I am still bleeding from the injury. And I will continue bleeding until the day I die, and am healed at last in Love’s Presence.

I stood in that yard, and I heard the hateful rantings of a demonic joy that was and is a part of America. And, also a part of me. There are sins we have sinned for which we cannot atone, cannot expect forgiveness as though it is a right or privilege. To think we can expect such forgiveness is to mock not only history, but also to mock Christian theology and the meaning of the Cross. As Kierkegaard reminds us in his “Training in Christianity,” to embrace the Word of God is also to embrace the offense to others that Word embodies. That is why Martin Luther King died. His message of love carried the offense of the cross with it, the offense that making visible the oppressed, dispossessed, and marginalized always creates in an unjust society in an unjust world. Better for one man to die…

We are without excuse. The sooner we realize we are without excuse, the sooner healing can begin. Will we ever admit that the death of Martin Luther King was intrinsically part of the American Dream, that the two were woven together in a way that too many of us still want to hang onto?

I do not know the answer. All I know is that, as much as I loved that child, as much as I remember his cool and analytical reaction to what he experienced, I also know I cannot and would not return to the world from which he came. I am awake, and I am awakening. Love demands I stay vigilant. Tears are good; confession cleanses the soul. But deeply dwelling upon and considering these things is better. And acting on them is better yet. There is still so much work to be done, as the recent lack of comprehension over the Jeremiah Wright sermons illustrates.

I do not hate Mr. Corman. Rather, the older I get the more I realize just how hard it is for a single person to battle his or her culture’s wisdom, its preconceptions and self-protective blindness. I do not hate myself for my naivety. But I do hate the naivety itself, and I pray that Love continues to strip it from me so that I might be at least a mildly adequate container for a drop or two of love in this broken and terrified world.

I do not hate Mr. Corman. Rather, the older I get the more I realize just how hard it is for a single person to battle his or her culture’s wisdom, its preconceptions and self-protective blindness. I do not hate myself for my naivety. But I do hate the naivety itself, and I pray that Love continues to strip it from me so that I might be at least a mildly adequate container for a drop or two of love in this broken and terrified world.

God bless you, Dr. Martin Luther King. I miss you every day of my life. I look forward to knowing you one day soon.

* Not his real name