The newly-named “Wilson Abbey” at 935 W. Wilson will soon open its doors to our Uptown neighborhood with everything from a fascinating coffee shop to a massive multi-purpose meeting room, concert venue, medium-sized theater, recording studio, rentable office space, and much much more. To say we’re excited about this fresh expression of creative energy in the heart of Uptown would be an understatement!

The newly-named “Wilson Abbey” at 935 W. Wilson will soon open its doors to our Uptown neighborhood with everything from a fascinating coffee shop to a massive multi-purpose meeting room, concert venue, medium-sized theater, recording studio, rentable office space, and much much more. To say we’re excited about this fresh expression of creative energy in the heart of Uptown would be an understatement!

The new Wilson Abbey building has an old and astonishing story, one rooted in boom and bust, glamor and gangland, police scandals and aromatic candles, flappers and flim-flammers and faith.

This is just some of that story.

All About Automobiles!

The Uptown, Chicago area as the 1920s approached was on the verge of becoming Chicago’s second-hottest nightspot after Chicago’s downtown, and Wilson Avenue just off Lake Michigan would be the heart of that new economic vitality. But even in the late ‘teens one of the biggest portents of the coming boom was increasingly everywhere: Cars. In 1917, there were (according to automotive journalist Fred Covlin) “127 different makes of American automobiles on the market” (compared to a mere dozen only thirty years later). In the late ‘teens, making — and selling — cars was open to anyone with know-how. Which leads in 1916 to the first whisper of the Wilson building’s birth:

Robert M. Fatz intends to improve the property on Wilson avenue, 175 feet east of Sheridan road, 100×192 feet in extent, north front, he recently acquired from the Sheridan Road Theater company, with a two story reinforced concrete building for automobile salesroom purposes, to be occupied by Louis Geyler & Co. agents for the Hudson automobile. The building will cost about $90,000. The transaction was closed by Charles O. Goss of E. A. Cummings & Co. (Chicago Daily Tribune, July 28, 1916, pg. 14.)

Our first historical surprise came when discovering the architects behind the future 935 W. Wilson’s design. Cornelius W. Rapp (d.1926) and George Leslie Rapp (1878–1942) are associated with two of Uptown’s most famous still-extant buildings — the Riviera (1918) and the Uptown Theater (1925). But their world-wide fame is linked to 1921′s Chicago Theater (and the still-original bright sign which was lifted by the movie “Chicago” as a logo) and New York City’s Paramount Theater / Tower in Times Square. The Rapp Brothers will forever be associated with theaters in architectural history, working with the Balaban and Katz Corporation (who eventually would merge with Paramount Pictures) to create some 400 Theaters in America.

Our first historical surprise came when discovering the architects behind the future 935 W. Wilson’s design. Cornelius W. Rapp (d.1926) and George Leslie Rapp (1878–1942) are associated with two of Uptown’s most famous still-extant buildings — the Riviera (1918) and the Uptown Theater (1925). But their world-wide fame is linked to 1921′s Chicago Theater (and the still-original bright sign which was lifted by the movie “Chicago” as a logo) and New York City’s Paramount Theater / Tower in Times Square. The Rapp Brothers will forever be associated with theaters in architectural history, working with the Balaban and Katz Corporation (who eventually would merge with Paramount Pictures) to create some 400 Theaters in America.

How did such heavy hitters, architecturally speaking, get involved in designing an auto dealership? One can only guess; their greatest work was still ahead of them in 1916 when plans first began being worked on for the future home of Hudson cars in Uptown.

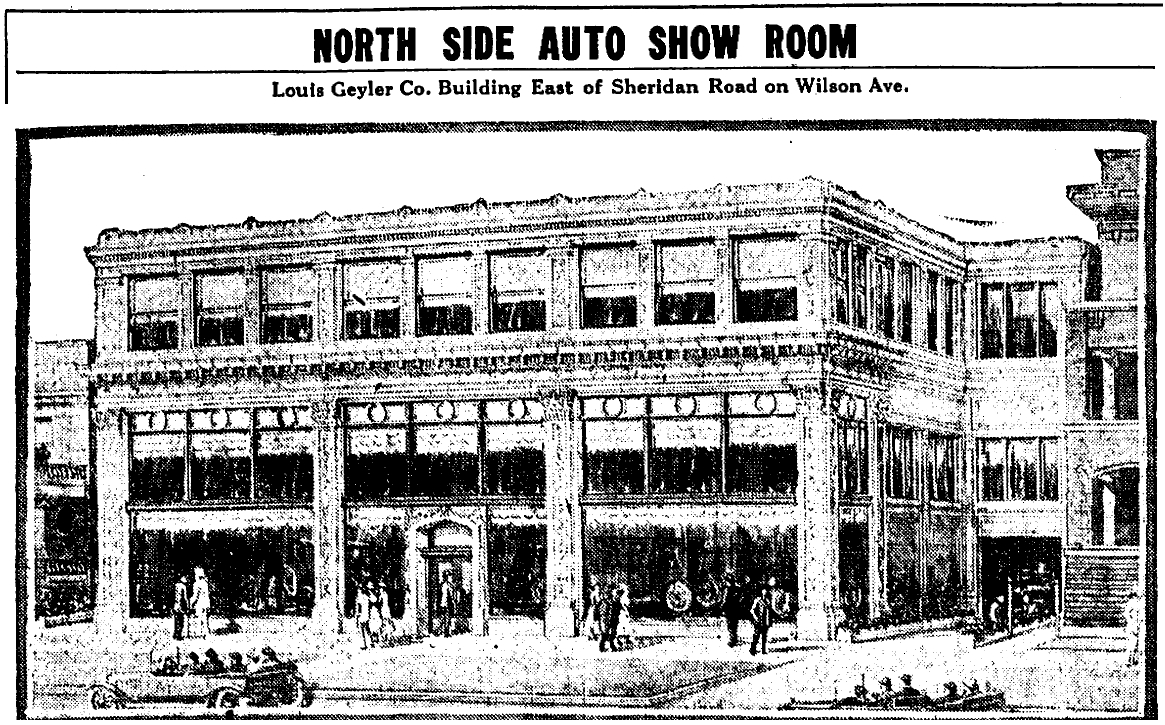

Building was underway by early 1917. In January, reporting on Louis Geyler’s Hudson dealership expansion in Chicago, the Daily Trib noted: “[P]lans of the Chicago distributor are for a handsome service building at Sheridan Road and Wilson Avenue, work on which is going forward rapidly.” (Daily Tribune, January 6, 1917, p. 3) By September of that year, the Trib offered a drawing of the building as it would look complete:

An attractive building is being erected for th Louis Geyler company on Wilson avenue just east of Sheridan Road to serve as a sales and display room. It will occupy a lot with a frontage of 100 feet by 194 feet in depth. The building was designed by C. W. and George L. Rapp and its cost is placed at about $125,000. The main floor is given over entirely to service and will be without any elevators. The display room for cars is 100×40 feet, has a ceramic floor and is carried out in the modern French style. There is to be a large fountain in the center and along the rear of the room is a gallery. E. A. Cummings and Co. are the agents. (Chicago Daily Tribune, Sep 2, 1917, p. D21.)

The October 16, 1917 Hudson Triangle bragged about the new Wilson facility and offered this arty but somewhat confusing view of its interior. The fountain seemed to be the main focus. (Click to enlarge.):

Humility was not in evidence in the article accompanying the above pictures:

The finest retail automobile saleroom in Chicago, and probably in the United States, has just been opened by the Louis Geyler Company, Hudson distributors.

It is located on Wilson Avenue, just off Sheridan Road, in the heart of the finest residence district of Chicago. Other companies have had small service stations in this vicinity, but Mr. Geyler is the first one to appreciate the importance of having a well-equipped salesroom and service station on the North Side, where the greater proportion of all retail sales are made.

The new Salesroom stands on a lot 100×200 feet deep. The show room is 75×40 feet with a 20 foot ceiling. There are no columns in the show room, and it is said to be the largest piece of reinforced concrete in the country.

The rich heavy purple drapes over cream curtains, the mosaic tile floor, and a color scheme that harmonizes perfectly, form a gorgeous setting for Hudson limousines or town cars. The whole plan of architecture and the furnishing s were carried out under the directions of one of Chicago’s foremost designers.

Directly over the salesroom is the Used Car Salesroom, a replica of the main salesroom, but not so elaborately furnished. Back of this the Used Car Department, where cars taken in on trade are refitted and rebuilt. Ramps lead to the second floor.

Just back of the salesroom on the main floor is a large service room There is no garage entrance on the street. Both the exits and the entrances are set well back from the street on either side of the salesroom.

An interesting feature is that inside doors in the garage, and also the exit and entrance doors, are electrically controlled from a hanging office in the shop by the timekeeper. No car is permitted to enter or leave without his O.K. There can be no argument at the exit door. The driver must have proper credentials in order to get the release of his car.

Shower baths have been provided for the mechanics.

The offices of the salesmen and the manager are located o the balcony. Just above is a large commodious stock room for parts and accessories

The building and land represent an investment of nearly $200,000. It has taken approximately 18 months from the time the land was purchased to the completion of the building, and so Mr. Geyler has a two years’ start of any of his competitors on the North Side. (Hudson Triangle, p. 4)

Just as now, companies found ways to cross-advertise. One of those ways Geyler apparently found was to allow his name to be coupled with the stone he purchased for the building. This made — again — for some serious advertising hype that does actually have some information about the building embedded within it.

Counterfeit… Hmmm. They hadn’t invented styrofoam yet…

Counterfeit… Hmmm. They hadn’t invented styrofoam yet…

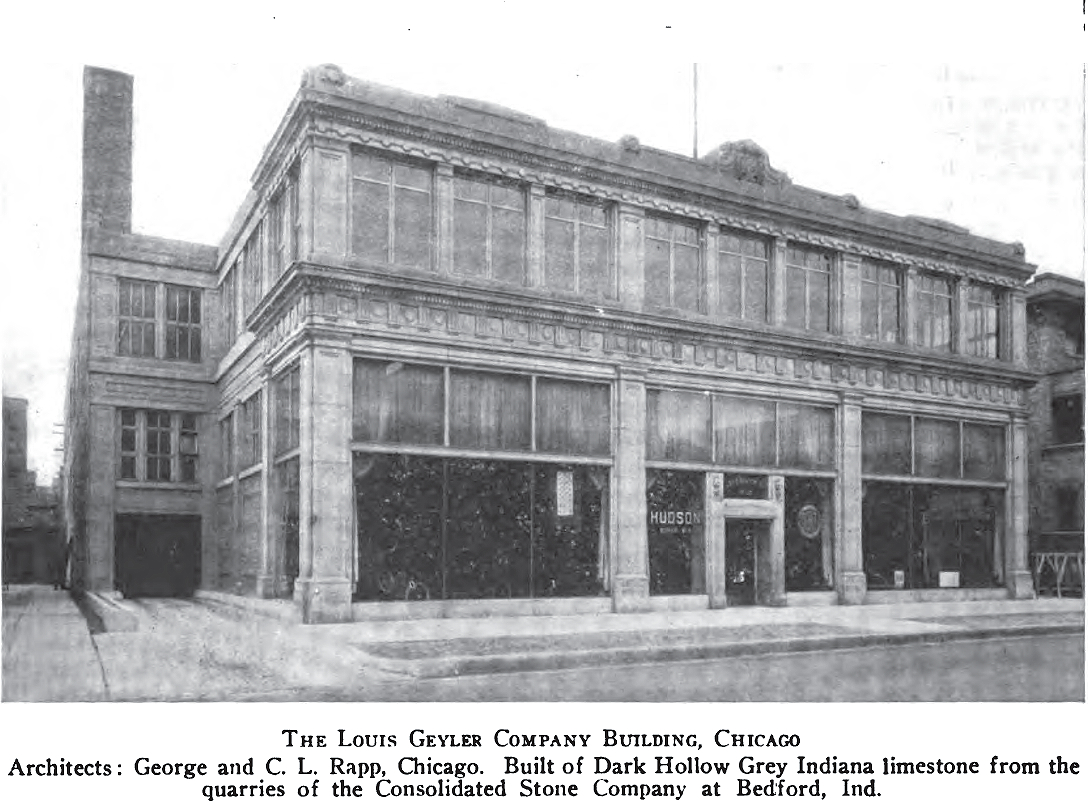

A few pages later, the same publication (Stone: an Illustrated Magazine, Vol 39, p. 269) gave the less usual angle photography-wise, showing the left garage entrance rather than the right.

The Mysterious Mandarin Gardens

Wilson Avenue had gone from being a business street in a residential area to Chicago’s swinging hot spot. During the 20s the street would become dense with bars, restaurants, and dance halls. Hudsons and (as of August 1919) Oakland-Phillips autos were advertised and sold for a time which proved to be short–perhaps because an auto dealer in the midst of this booming nightclub scene was out of place. (Chicago Daily Tribune, August 17, 1919, p. E8.) The exact date the last car was sold from the dealership is unknown at present. But as early as 1920 — only a few years after the Hudson dealership started selling cars — Geyler entered into  negotiations to sell the property to Chin Foin, a Chinese restauranteur. Mr. Foin did indeed lease the 931-33 address. The Economist (Vols 65 – 67) tracked the sale as of December 1920, elements of which changed from an initial promised outright purchase by the buyer to a longer-term lease to buy plan. The building (most of it, anyway) was to become “The Mandarin Gardens.” The December 12, 1920 Tribune enthused:

negotiations to sell the property to Chin Foin, a Chinese restauranteur. Mr. Foin did indeed lease the 931-33 address. The Economist (Vols 65 – 67) tracked the sale as of December 1920, elements of which changed from an initial promised outright purchase by the buyer to a longer-term lease to buy plan. The building (most of it, anyway) was to become “The Mandarin Gardens.” The December 12, 1920 Tribune enthused:

GORGEOUS CAFE PLANNED FOR JUNIOR LOOP: Mandarin Gardens to Cost Over $250,000.

One of the most luxurious and best equipped restaurants in the middle west, to cost more than a quarter of a million, is the latest contemplated addition to the gayety and glamour of our junior loop to the north–the Wilson avenue district.

Work will start Jan. 1 from plans by Minchin & Weller, Inc., architects and engineers, in transforming the modern two story concrete structure at 931-33 Wilson avenue, just west of Sheridan road and across from the Sheridan Plaza, now occupied by the owner, the Louis Geyler company, as a motor salesroom, into a gorgeous cafe. It will be called Mandarin Gardens.

The article went on to say that Foin’s plan was for a fully American restaurant, complete with music and dancing as well as dining. It was to be finished as of April 1, 1921. Just one block down the street, the Via Lago at 837 Wilson wowed its patrons with a lighted-from-beneath dance floor (shades of John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever!). The proposed Mandarin Gardens would, according to the article, outdo even that.

The building is 100×200, and, with the exception of space for a shop on each side of the main entrance, all the space will be sued by the cafe. A splashing fountain [the same one the Hudson folks had placed there?] will greet visitors as they enter the lobby. There will be a stage at the south end, with a glass floor in front of it for exhibition dances with colored lights.

There will be one of the largest dancing spaces for guests of any cafe in the city; also a mezzanine floor with two private banquet rooms and tables. The restaurant will accommodate 1,200 guests at one time….

[S]aid Mr. Foin, “Now we’ve cut out the far east features and operate a strictly American restaurant, and that’s what the Mandarin Gardens will be.” [p. H18]

But the mystery is this: Apparently, the Mandarin Gardens (unlike other successful restaurants Mr. Foin had elsewhere in Chicago) never actually existed. I’m not alone, at least, in fruitlessly searching for evidence that it ever did. (See Jan Whitaker’s Anatomy of a Restauranteur: Chin Foin.) But as we will see, it is proven that he did lease, and probably bought, the building.

Mr. Foin suffered a tragic and untimely death only a few years later, in 1924, when he stepped into what turned out to be an empty elevator shaft. Perhaps his plans for the lovely-sounding Mandarin Gardens would have come to fruition otherwise. Instead, October 21 of 1924, the Chicago Daily-Tribune reported on the transfer of the property from Foin’s surviving family:

The widow of Chin F. Foin, loop Chinese restaurateur, Mrs. Yokeluad W. Foin, and her children…. yesterday leased the store and mezzanine floor at 931-35 and the east half of the store at 937 Wilson avenue to George A. Twist. The term rental from Oct. 1, 1924 to Dec. 29, 1930, will be $33,958. Mr. Twist has an option to extend the term fifteen years. He will sublease the property for restaurant purposes.

And by the next year the rental of smaller spaces within the building was evident in the Tribune’s classified ads section.

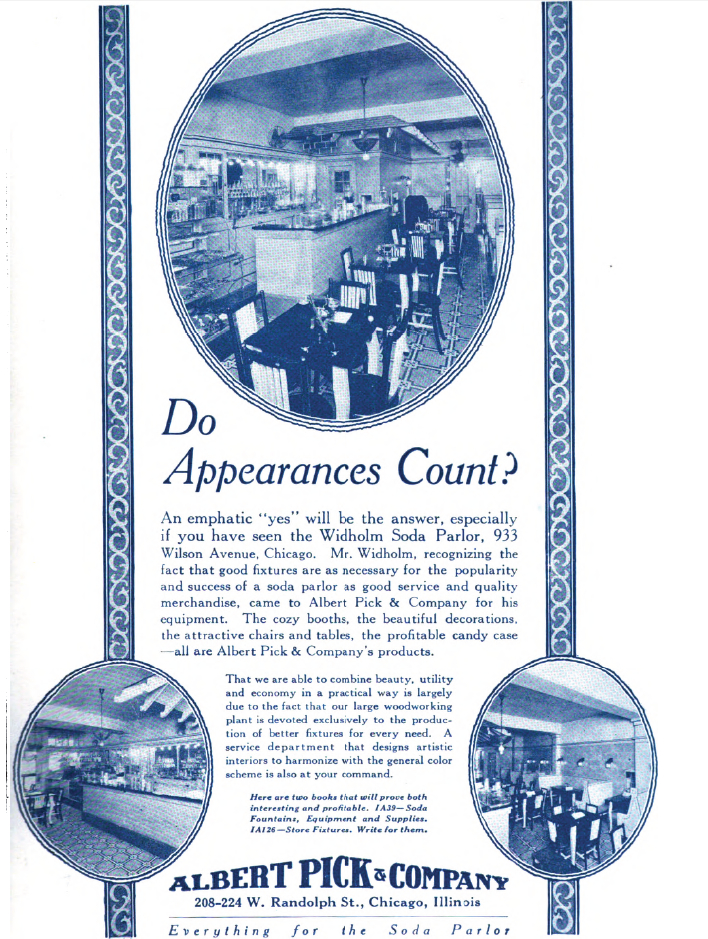

We do, again thanks to creative cross-pollenizing by advertisers, have even earlier evidence there was at least one renter the Foin family apparently accepted. The Widholm Soda Parlor, located at 933 Wilson avenue as early as September 1921, was pictured when this ad aimed at ice cream and soda shop owners was published:

Such a nice little ice cream parlor… but what would happen to it and 931-39 Wilson would not be sweet.

THE SERIES CONTINUES:

(Wild History – A Literary Aside #1: Ben Hecht’s “Nirvana”)

(Wild History – Part 2: Jesus People USA’s Wilson Abbey Was Once the Vice Palace of Uptown)

(Wild History – A Literary Aside #2: Edna Ferber’s “Home Girl“)

(Wild History, Part 3: Coming soon….)

Pingback: Wild History (Part 2): JPUSA’s Wilson Abbey now, but was once Uptown’s Vice Palace

Hello. I am the granddaughter of Chin F. Foin and I am doing a storytelling piece on him and am trying to figure out why he would buy this Wilson building when prohibition had just begun.

And trying to figure out why Mandarin Gardens never happened except he ran out of money? In 1924 he sold his mansion and was moving his family to China. They never left because he died the night before they were leaving.

Any ideas? Was he in trouble? danger? murdered? Thanks.

We are dealing with newspapers here, Nancy… which is where I got much of my info. The Chicago Tribune in particular has been available via the Chicago Library system for cardholders. (I’ve not been on line there in a long time now.)

As I recall this story (remember, the “official” one / newspaper one in white America of yesteryear), he stepped into an elevator shaft that didn’t have an elevator in it. If that sounds suspicious… well, yes, I’d agree it does.

I was not aware of your information, which I presume comes from his descendants and sources closer than I was to this story when I relied on the Tribune. Please do let me/us know if you are able to piece together a more accurate narrative than what I have here. (That shouldn’t be hard, due to my paucity of resources as well as the fact I didn’t drill very deeply into any single person or vignette in this overview type article).

Blessings.