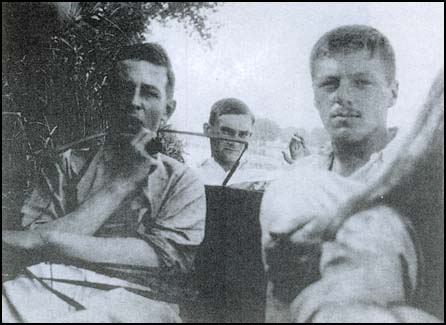

C. S. Lewis in 1917, left, with friend Earnest Moore during World War I. Moore was later killed, as were many of Lewis' friends. Lewis, due a promise to Moore, cared for (for a time may have loved) Moore's mother.

Threads of despair and fantasy are woven together in a poetic work C. S. Lewis, best known for his post-conversion Christian writings, penned as a young man just back from World War I. In 1919, Spirits in Bondage was published under the pseudonym “Clive Hamilton.” It might be a stretch to say that this collection is edifying (at least in the usual sense of that word). Lewis himself, writing in 1918 to a friend (Arthur Greeves), said Spirits in Bondage was:

“mainly strung around the idea that I mentioned to you before–that nature is wholly diabolical &

malevolent and that God, if he exists, is outside of and in opposition to the cosmic arrangements.” [preface, “Spirits in Bondage.”]

A few things to remember about Lewis, even at this stage of his intellectual life — he was fascinated by mythology and an avid student of Norse mythology in particular, he studied philosophy diligently but was not strictly speaking a full-blown materialist, and finally he was a very young man whose thinking was in a very formative (one might even say confused) stage. What might confuse the reader about the poems is how many of them have passages praising nature, even praising an ill-defined God. The underlying themes, however, help to clear at least some of that confusion. The interplay is between harsh modernist reality and a faerie-tale dreamer’s fantasy world, reality trumping fantasy at nearly every turn… but perhaps not all turns.

Lewis doesn’t want the reader to make any mistake as to the overall message he wishes to impart. Two lines open the book:

“The land where I shall never be

The love that I shall never see”

The cycle is constructed in three sections: “The Prison House”, “Hesitation,” and “The Escape.” (These three are made of twenty-one, three, and sixteen poems respectively.) The titles are intriguing, leading us to ask what the nature of the Prison is, what the hesitation is over, and how the escape may be effected. But we’re to be disappointed. I don’t think Lewis ever got around to answering those questions, even to his own satisfaction, so the section titles seem less than useful.

Lewis had originally, while still on the front during WWI, envisioned the book’s title as Spirits in Prison. The Prison House section, appropriately enough, begins with its apparent warden, Satan / Nature. It seems highly unlikely that Lewis is referring to a literal devil, though he certainly later on did write at length in The Screwtape Letters, Mere Christianity, and elsewhere about a Satan he did believe was literal. The “devil” of these poems, as he makes very clear in the very first line, is a harshly impersonal Nature.

Satan Speaks

I am Nature, the Mighty Mother,

I am the law: ye have none other.I am the flower and the dewdrop fresh,

I am the lust in your itching flesh.I am the battle’s filth and strain,

I am the widow’s empty pain.I am the sea to smother your breath,

I am the bomb, the falling death.I am the fact and the crushing reason

To thwart your fantasy’s new-born treason.I am the spider making her net,

I am the beast with jaws blood-wet.I am a wolf that follows the sun

And I will catch him ere day be done.

Death, not life, is the victor. The spider catches the fly, creation returns all its creatures to the dust from where they came, even the sun will in the end be “consumed” by maximum entropy.

The poem, “French Nocturne (Monchy-Le-Preux),” is overtly an observation of war as a participant in its carnivorous folly. The poem title’s inclusion of a French town reveals where Lewis spent a portion of his war near the area where he was badly wounded by shell shrapnel April 15, 1918 (his close comrades were killed):

Long leagues on either hand the trenches spread

And all is still; now even this gross line

Drinks in the frosty silences divine

The pale, green moon is riding overhead.The jaws of a sacked village, stark and grim;

Out on the ridge have swallowed up the sun,

And in one angry streak his blood has run

To left and right along the horizon dim.…What call have I to dream of anything?

I am a wolf. Back to the world again,

And speech of fellow-brutes that once were men

Our throats can bark for slaughter: cannot sing.

Some commentators (Bruce L. Edwards, for instance) suggest that Lewis, despite his dark view of war as revealer of life’s cruel meaninglessness, was not a complete modernist who overtly accepted despair as his only guide. Adam Barkman explores this period of Lewis’ life as one very much in flux philosophically, though still more affected by classical influences than by modernist despair. Despite his formidable developing intellect, Lewis had – at that time – found an answer little different than that found by the rest of his generation. It was a mash of variant ideas, some (it appears to me) contradictory. For instance, at times Lewis seems to believe in some sort of “spirit” of man — a non-defined spirit but with post-mortem properties — while also disbelieving in an afterlife. One poem is called “Spooks” (ghosts), presenting us with a man who only gradually realizes he is dead as he haunts the street his lover lives on. I do not pretend here to fully explore the sources for those ideas.

Cynicism of a most desperate kind was not just intellectual posturing; Lewis and his literary contemporaries had seen in the peculiar horrors of WWI’s mustard gas, trenches, bullets, bayonets, and mortar shells the dismantling of romantic illusions. They valued the illusions… but as illusions. There is little in these poems to show Lewis had found a different, less despairing, path than his generation. Lewis at the time was a blurry Agnostic-Atheist, so no spirituality – at least, none in these poems – provided shelter from his war experience. Perhaps the best known German literary voice of WWI, Erich Remarque (All Quiet on the Western Front), sounds very similar to Lewis in his also war-related work, 3 Comrades. Remarque uses music as well as nature to illustrate the beautiful and filled with longing illusion, rooted in the reality of meaningless death:

The music enchanted the air. It was like the south wind, like a warm night, like swelling sails beneath the stars, completely and utterly unreal… It made everything spacious and colourful, the dark stream of life seemed pulsing in it; there were no burdens any more, no limits; there existed only glory and melody and love, so that one simply could not realize that, at the same time as this music was, outside there ruled poverty and torment and despair.

Then there is Ernest Hemingway, likely the most well-known writer on WWI of all, who in Farewell to Arms puts nihilism into it’s blunt form:

The world breaks everyone … those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

Lewis’ vision is just as dark in his poem “Apology,” an apology only in the classic sense, a defense of “why I tell / Of nothing glad nor noble in my verse / To lighten hearts beneath this present curse.” He paints a picture of “green field” but torn by graves, fairly obviously a war reference. In light of such realities, the good moments seem deceptions.

All these were rosy visions of the night,

The loveliness and wisdom feigned of old.

But now we wake. The East is pale and cold,

No hope is in the dawn, and no delight.

What was C. S. Lewis’ experience of World War I? Lewis was reticent to talk about the war, though in Surprised by Joy, (his 1955 biography) he does address it somewhat:

Through the winter, weariness and water were our chief enemies. I have gone to sleep marching and woken again and found myself marching still. One walked in the trenches in thigh gum boots with water above the knee; one remembers the icy stream welling up inside the boot when you punctured it on concealed barbed wire. Familiarity both with the very old and the very recent dead confirmed that view of corpses which had been formed the moment I saw my dead mother. I came to know and pity and reverence the ordinary man: particularly dear Sergeant Ayres, who was (I suppose) killed by the same shell that wounded me. I was a futile officer (they gave commissions too easily then), a puppet moved about by him, and he turned this ridiculous and painful relation into something beautiful, became to me almost like a father. But for the rest, the war – the frights, the cold, the smell of H. E. (high explosives), the horribly smashed men still moving like half-crushed beetles, the sitting or standing corpses, the landscape of sheer earth without a blade of grass, the boots worn day and night till they seemed to grow to your feet – all this shows rarely and faintly in memory. It is too cut off from the rest of my experience and often seems to have happened to someone else.

That description, harsh enough, seems muted both by time and an emotional disconnect to which Lewis admits. In contrast an officer friend of the poet T. S. Eliot sent the latter correspondence which Eliot then forwarded–while the War still raged–to The Nation for publication. The officer speaks, in unsmiling jest, of the civilians who approach him meaning to draw him out on his experiences at the front. It is striking how similar some of this description, though far more graphic, is to Lewis’:

“[Y]ou are tempted to give them a picture of a leprous earth, scattered with the swollen and blackening corpses of hundreds of young men. The appalling stench of rotting carrion, mingled with the sickening smell of exploded lyddite and ammonal. Mud like porridge, trenches like shallow and sloping cracks in the porridge – porridge that stinks in the sun. Swarms of flies and bluebottles clustering on pits of offal. Wounded men lying in the shell holes among the decaying corpses: helpless under the scorching sun and bitter nights, under repeated shelling. Men with bowels dropping out, lungs shot away, with blinded smashed faces, or limbs blown into space. Men screaming and gibbering. Wounded men laughing in agony on the barbed wire, until a friendly spout of liquid fire shrivels them up like a fly in a candle. But these are only words, and probably only convey a fraction of their meaning to their hearers. They shudder and it is forgotten.” [T. S. Eliot’s Letter to The Nation]

In one other place, at least, Lewis tangentially touches on his war experience while trying to describe the most painful events of his life; those surrounding the illness and death of his beloved wife Joy Davidman. In his 1961 A Grief Observed, Lewis is unpacking the powerful temptation toward disbelief in a God who is Good. Within that context he ruminates upon the difference between grieving (a mind, or psychological, pain) and the pain of the body.

Grief is like a bomber circling round and dropping its bombs each time the circle brings it overhead; physical pain is like the steady barrage on a trench in World War One, hours of it with no let-up for a moment. Thought is never static; pain often is.

It is tempting–no, correct–to say there’s at least a slight nuance in Lewis’ interpretation of reality vs. Remarque, Hemingway, and the other “Lost Generation” writers whom WWI affected so profoundly. There is the touch of a pagan about Lewis, pagan in the old sense of that word. One won’t catch Lost Generation writers talking much about faeries or mythical supernatural beasts and heroes. Lewis never stops talking about them. In “The Satyr,” for instance:

When the flowery hands of spring

Forth their woodland riches fling,

Through the meadows, through the valleys

Goes the satyr carolling.From the mountain and the moor,

Forest green and ocean shore

All the faerie kin he rallies

Making music evermore.

Yet even in what appears an optimistic hymn to Nature’s glories, the poem ends on a subtle note of ennui. One must not forget the volume’s title.

Lewis, in his second-to-final poem of the book, “Tu Ne Quaesieris” (title is from Horace’s “Carpe Diem,” and translates as “Ask not–we cannot know”), plays with ideas that on their face appear more Hindu than Christian. Yet keep in mind the somewhat confused twin themes of modernist despair vs. the overtly spiritual yearning for the Other; it’s not only Christianity providing the young poet with symbols he subverts to his own uses:

If still my narrow self I be

And hope and fail and struggle still,

And break my will against God’s will,

To play for stakes of pleasure and pain

And hope and fail and hope again,

Deluded, thwarted, striving elf

That through the window of my self

As through a dark glass scarce can see

A warped and masked reality?

But when this searching thought of mine

Is mingled in the large Divine,

And laughter that was in my mouth

Runs through the breezes of the South,

When glory I have built in dreams

Along some fiery sunset gleams,

And my dead sin and foolishness

Grow one with Nature’s whole distress,

To perfect being I shall win,

And where I end will Life begin.

Lewis, the doubter, nonetheless seems to be signaling a belief in Atman (the Hindu concept of self / selves / God). Later on, in the 1941 Mere Christianity, Lewis rejected the Hindu Pantheism from which this teaching comes in blunt terms: “Confronted with a cancer or a slum the Pantheist can say, ‘If you could only see it from the divine point of view, you would realize that this also is God.’ The Christian replies, ‘Don’t talk damned nonsense.’”

And Lewis immediately, anticipating the skeptic’s next objection, expands that 1941 argument further to also address Atheism’s complaint against a Good God vs evil in the world:

My argument against God was that the universe seemed so cruel and unjust. But how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing this universe with when I called it unjust? If the whole show was bad and senseless from A to Z, so to speak, why did I, who was supposed to be part of the show, find myself in such violent reaction against it? A man feels wet when he falls into water, because man is not a water animal: a fish would not feel wet.

Of course I could have given up my idea of justice by saying it was nothing but a private idea of my own. But if I did that, then my argument against God collapsed too— for the argument depended on saying that the world was really unjust, not simply that it did not happen to please my private fancies. Thus in the very act of trying to prove that God did not exist—in other words, that the whole of reality was senseless—I found I was forced to assume that one part of reality—namely my idea of justice—was full of sense.

As a teen-ager, this writer read Mere Christianity and was impressed by these arguments in particular. Though that book as a whole has problems, I still am frankly impressed by the above as credible. (I make that confession knowing it may mean I’m tossed on the intellectual trash pile by some reading this.)

But I’m also reminded of just where Lewis failed to move me, even today often fails. Lewis — despite toying with a despairing tone in places throughout Spirits in Bondage — did not like his contemporaries feel the full bite of despair. Not even, it appears, on the battlefields of France. Nor is there great evidence he followed or interacted much with another group inspired by despair, the existentialists. His classical focus seems to have short-circuited any ability to resonate deeply even later on with the Christian elements within that movement, such as Kierkegaard, Gabriel Marcel, or the French novelist Francois Mauriac. One suspects his antipathy toward T. S. Eliot was in part based on the latter’s intensely existential leanings in “Wasteland” and other poems.

I think all of us have an alternative belief system, a place where we would go if we were to discard our faith (whatever faith it might be). I don’t know what C. S. Lewis as a young man believed… any more than I suspect he himself knew. He was still in formation. But I do know that if I were to lose my belief in the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and all that went before it in the New Testament narratives, I would be left with nothing but nihilism. Despair would be my constant companion and a gentle hedonism my rule of life… up until I no longer saw that life as worth living. Lewis might have ended up a Pantheist, or he might have ended up an Atheist, but I think (admitting the ridiculous nature of this line of contemplation) he’d have rejected nihilism.

It is not in any way Lewis’ fault that his own youthful failure to despair — in great contrast to many of the times’ literary and philosophical voices — means I cannot find in him a close traveling companion, intellectually or existentially speaking. My own intellect is not that of Lewis’ and my own haunting is a subjective “alternative” reality which doesn’t necessarily have an objective basis to it. That is, there is no immutable set of reasons that — should Christianity be false — nihilism makes more sense than another alternative. It is simpler than that. Human beings are all finite and unique, and the ghosts we each find haunting us require others who know those same ghosts… Or at least similar ones.

Intriguingly, it may be that Lewis’ closest encounters with despair came late in his Christian life. That idea was caricatured in the movie “Shadowlands,” which presumed to offer a biography of sorts re Lewis’ marriage to Joy Davidman and crisis of faith after her death. The reality is far better examined through Lewis’ own recounting of it — unpoetic, starkly real, stated in the most everyman terms — in “A Grief Observed.” There, he mourns his wife’s loss while simultaneously encountering assaults upon his intellect and emotions. Death, Despair’s ultimate companion, is his interlocutor — as this longer passage shows:

Sometimes it is hard not to say, ‘God forgive God.’ Sometimes it is hard to say so much. But if our faith is true, He didn’t. He crucified Him.

Come, what do we gain by evasions? We are under the harrow and can’t escape. Reality, looked at steadily, is unbearable. And how or why did such a reality blossom (or fester) here and there into the terrible phenomenon called consciousness? Why did it produce things like us who can see it and, seeing it, recoil in loathing? Who (stranger still) want to see it and take pains to find it out, even when no need compels them and even though the sight of it makes an incurable ulcer in their hearts? People like H. herself, who would have truth at any price.

If H. ‘is not,’ then she never was. I mistook a cloud of atoms for a person. There aren’t, and never were, any people. Death only reveals the vacuity that was always there. What we call the living are simply those who have not yet been unmasked. All equally bankrupt, but some not yet declared.

But this must be nonsense; vacuity revealed to whom? Bankruptcy declared to whom? To other boxes of fireworks or clouds of atoms. I will never believe—more strictly I can’t believe—that one set of physical events could be, or make, a mistake about other sets.

No, my real fear is not of materialism. If it were true, we—or what we mistake for ‘we’—could get out, get from under the harrow. An overdose of sleeping pills would do it.

I am more afraid that we are really rats in a trap. Or, worse still, rats in a laboratory. Someone said, I believe, ‘God always geometrizes.’ Supposing the truth were ‘God always vivisects’?

Sooner or later I must face the question in plain language. What reason have we, except our own desperate wishes, to believe that God is, by any standard we can conceive, ‘good’? Doesn’t all the prima facie evidence suggest exactly the opposite? What have we to set against it?

We set Christ against it. But how if He were mistaken? Almost His last words may have a perfectly clear meaning. He had found that the Being He called Father was horribly and infinitely different from what He had supposed. The trap, so long and carefully prepared and so subtly baited, was at last sprung, on the cross. The vile practical oke had succeeded.

And here we see clearly the same ghosts that haunted C. S. Lewis as a young man and Atheist/Pantheist still haunted him as a sixty-plus year old and Christian. His haunting was not nihilism (no God, and therefore no meaning); rather it was an even more terrifying temptation toward a God of Evil, that old laughing, capricious satanic Nature-god with whom Spirits in Bondage opens, a vivisectionist God who enjoys inflicting pain upon his creatures. Images of the goddess of destruction, Kali, come to mind.

Lewis does not neatly explain away this ghost. All of us can dispense with the ghosts of others — it is effortless, because the ghost is not our bogey, not our 2 a.m. torturer, not our secret doubt and tormentor. But our own ghosts we must either speak of honestly or not at all:

I wrote that last night. It was a yell rather than a thought. Let me try it over again. Is it rational to believe in a bad God? Anyway, in a God so bad as all that? The Cosmic Sadist, the spiteful imbecile?

I think it is, if nothing else, too anthropomorphic. When you come to think of it, it is far more anthropomorphic than picturing Him as a grave old king with a long beard. That image is a Jungian archetype. It links God with all the wise old kings in the fairy-tales, with prophets, sages, magicians. Though it is (formally) the picture of a man, it suggests something more than humanity. At the very least it gets in the idea of something older than yourself, something that knows more, something you can’t fathom. It preserves mystery. Therefore room for hope. Therefore room for a dread or awe that needn’t be mere fear of mischief from a spiteful potentate. But the picture I was building up last night is simply the picture of a man like S.C.—who used to sit next to me at dinner and tell me what he’d been doing to the cats that afternoon. Now a being like S.C., however magnified, couldn’t invent or create or govern anything. He would set traps and try to bait them. But he’d never have thought of baits like love, or laughter, or daffodils, or a frosty sunset. He make a universe? He couldn’t make a joke, or a bow, or an apology, or a friend.

In the above Lewis confronts a real despair in the midst of battling his own ghosts. Soren Kierkegaard once wrote, “Someone in despair despairs over something. So, for a moment, it seems, but only for a moment. That same instant the true despair shows itself, or despair in its true guise. In despairing over something he was really despairing over himself, and he wants now to be rid of himself.” An animal in pain might want to chew off its own paw to escape the trap. A human in the midst of grief, or of clinical depression (that wasteland I suspect Lewis did not encounter), might consider “chewing off” her own consciousness via suicide. But again, the creature has to realize it is in pain / despair before it considers any radical remedy. Conversion, as Christian Catholic novelist Walker Percy observes, is a far more constructive solution for the despairer over self.

The final poem of Spirits in Bondage (quoted here in part) brings us back to the war, and back to that refusal to despair which — perhaps in the Kierkegaardian sense — is an even greater despair:

Sorely pressed have I been

And driven and hurt beyond bearing this summer day,

But the heat and the pain together suddenly fall away,

All’s cool and green.But a moment agone,

Among men cursing in fight and toiling, blinded I fought,

But the labour passed on a sudden even as a passing thought,And now-alone!

Ah, to be ever alone,

In flowery valleys among the mountains and silent wastes untrod,

In the dewy upland places, in the garden of God,

This would atone!I shall not see

The brutal, crowded faces around me, that in their toil have grown

Into the faces of devils-yea, even as my own-

When I find thee,O Country of Dreams!

Beyond the tide of the ocean, hidden and sunk away,

Out of the sound of battles, near to the end of day,

Full of dim woods and streams.

The “Country of Dreams” the young Lewis writes about — and he uses some variant of “dream” nearly thirty times in these poems according to my reckoning — are invariably self-deceptions from which the poet either awakens by reminding himself he is a “wolf” or else pleads for sleep and “lady Night” to give to him. Are these dreams the despair that Lewis, by not fully understanding, was most affected by? From the viewpoint of a Kierkegaard, who viewed Despair as a sort of Dawn even as it also was man’s sin that placed him within it, the failure to acknowledge despair was in fact the deepest despair of all. It was the failure to confront that terrible truth of Christianity, that to find your life you must lose it.

The older, grieving Lewis plainly understands this, on a level that is brutal in its honesty as what we see above preceded it:

The terrible thing is that a perfectly good God is in this matter hardly less formidable than a Cosmic Sadist. The more we believe that God hurts only to heal, the less we can believe that there is any use in begging for tenderness. A cruel man might be bribed—might grow tired of his vile sport—might have a temporary fit of mercy, as alcoholics have fits of sobriety. But suppose that what you are up against is a surgeon whose intentions are wholly good. The kinder and more conscientious he is, the more inexorably he will go on cutting. If he yielded to your entreaties, if he stopped before the operation was complete, all the pain up to that point would have been useless. But is it credible that such extremities of torture should be necessary for us? Well, take your choice. The tortures occur. If they are unnecessary, then there is no God or a bad one. If there is a good God, then these tortures are necessary. For no even moderately good Being could possibly inflict or permit them if they weren’t.

Either way, we’re [in] for it.

Reading the poems of this extraordinary young man, a soldier and wounded war veteran, a brilliant intellect and scholar even then, one can’t help but sense that C. S. Lewis had not yet discovered the right questions, much less the right answers — but more deeply had not discovered the true nature of his own ghosts. Like most of us, he continued wrestling with those ghosts throughout his life. While some of us found it hardest in our journey toward Christian faith to jump the hurdle of believing in any God, period, Lewis’ worst moments were in believing God was Good. Strangely, wonderfully, and perhaps predictably, the writings we best know of Lewis’ are filled with a sense of an abundant God, a God one might even call hedonistic and pagan and surely expressed in Nature, yet one also Wholly Good.

Yet I find myself driven to end with one more quote from the C. S. Lewis who was living if not in, next to, Despair. And in the midst of that dark night of his soul, he writes about goodness and God in a way that wrings the heart. Some might say he sounds a bit the heretic here; I say he is exorcising ghosts and in the process drawing our own ghostly selves closer and closer to the Holy Spirit of God:

It is often thought that the dead see us. And we assume, whether reasonably or not, that if they see us at all they see us more clearly than before. Does H. [his wife] now see exactly how much froth or tinsel there was in what she called, and I call, my love? So be it. Look your hardest, dear. I wouldn’t hide if I could. We didn’t idealize each other. We tried to keep no secrets. You knew most of the rotten places in me already. If you now see anything worse, I can take it. So can you. Rebuke, explain, mock, forgive. For this is one of the miracles of love; it gives—to both, but perhaps especially to the woman—a power of seeing through its own enchantments and yet not being disenchanted.

To see, in some measure, like God. His love and His knowledge are not distinct from one another, nor from Him. We could almost say He sees because He loves, and therefore loves although He sees.

Sometimes, Lord, one is tempted to say that if you wanted us to behave like the lilies of the field you might have given us an organization more like theirs. But that, I suppose, is just your grand experiment. Or no; not an experiment, for you have no need to find things out. Rather your grand enterprise. To make an organism which is also a spirit; to make that terrible oxymoron, a ‘spiritual animal.’ To take a poor primate, a beast with nerve-endings all over it, a creature with a stomach that wants to be filled, a breeding animal that wants its mate, and say, ‘Now get on with it. Become a god.’