Yet again! Wilson and Sheridan Avenues draw some less than wholly complementary (if not wholly critical either) attention from a lion of literature… or more properly in Henry Justin Smith’s case, journalism. Mr. Smith, along with having written some dozen books (the majority of them addressing the art of journalism), was also managing editor of the no longer extant (1875-1978) Chicago Daily News. Another journalist, Robert O’Connor, recently wrote of Smith’s vision: “Henry Justin Smith advocated for newspaper writing as an art as high as novels or poems. He saw his newspaper as a daily novel of life, written by a team of Balzacs. He believed that journalists wrote literature as profound and as important as poets and novelists.”

Smith, born June 19, 1875, would die February 9, 1936 — just five years after publishing the below chapter in his book, Chicago: A Portrait. Like most good print journalists, he kept his mug out of camera-range, so it is very hard to find it even on this photophilian web. His words — plus a nice illustration or two from the original book — will have to do. [Correction! Thanks to an archive of Chicago Daily News photos, Mr. Smith’s visage, left, is found!]

For those looking specifically for our “Wild History’s” geographical center, Uptown’s Wilson and Sheridan avenues, the sub-section marked “4″ will lead them there.

And of course when one’s finished the below, we have our previous “WILD HISTORY (Literary Aside #1): Ben Hecht” and WILD HISTORY (Literary Aside #2): Edna Ferber” — both of whom are also either rude or correct (not possibly both!) with their own Wilson and Sheridan stories. Then there’s OUR stories about Wilson and Sheridan and a certain building… starting with “Wild History, Part 1: JPUSA’s Wilson Abbey From Auto Dealership to Strip Club to New Uptown Gem.”

– + –

Chapter XVII of Henry Justin Smith’s “Chicago: A Portrait” – 1931

– + –

A little more than thirty-five years ago there lived a poet, in an old remodeled frame house out in the suburbs. The house “had all the modern conveniences, including a genial mortgage. About it were the oaks, in whose branches the birds had built their nests before Chicago was a frontier post. He could sit upon the ‘front stoop’ and look across vacant lots to where Lake Michigan beat upon the sandy shore with ceaseless rhythm. ”

Such is the picture drawn by Slason Thompson of the home of Eugene Field the poet, in a place deemed sufficiently far from the city so that he might dream there for a long time. The lot was large; it was a serene corner of earth. The birds sang happily. Flowers flourished. Field named the place “The Sabine Farm,” in what another biographer, Charles H. Dennis, calls “a mild Horatian jest.”

Earlier than that, Field and his family had a rented cottage a few blocks farther west, “in the green open spaces of Buena Park,” as Mr. Dennis describes the region of that day. The cottage, to quote Hamlin Garland, a frequent visitor, “swarmed with growing boys and noisy dogs.” And the poet’s bedroom overlooked a vacant lot belonging to his friend and landlord, Robert A. Waller, known as the founder of Buena Park. It was Field’s contemplation of the grassy area that inspired his lines:

Up yonder in Buena Park

There is a famous spot,

In legend and in history

Yclept* the Waller Lot.

There children play in daytime

And lovers stroll by dark,

For ’tis the goodliest trysting-place

In all Buena Park.

[* “called” or “named” — WS]

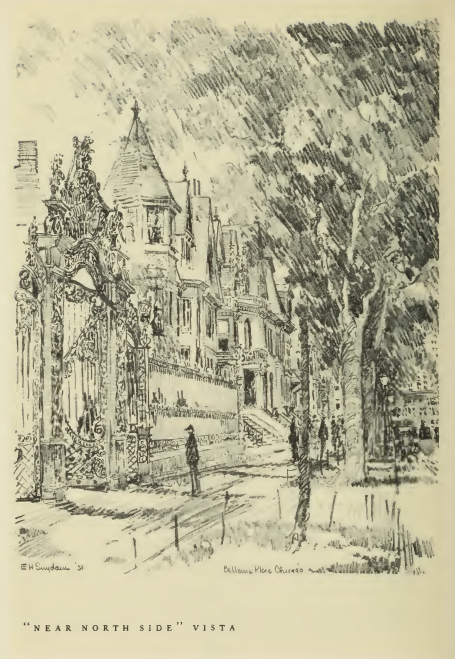

Mr. Field did not live long to enjoy the Sabine Farm. Had he occupied it until old age he would have found his place of retirement hemmed in by apartment-buildings, the street that passed it swarming with automobiles, and the green and charming landscape to the north virtually overspread with concrete, brick, and stone. A flat-building has replaced the Field homestead.

Regret it or not, all this is the work of a generation.

– 2 –

The city has pressed forward to the very border of Evanston; or rather, to Calvary Cemetery, the old Catholic burying-ground which intervenes. People still young can remember when Rogers Park, Edgewater, and Buena Park itself, were villages. Not long before, Lake View — now a mere place-name and a designation in tax books — had an identity too. Until not so many years ago the region still possessed its town hall, which stood at Halsted and Addison streets and boasted an assembly room in which the village life, artistic and religious, centered. In the seventies Lake View acquired the United States Marine Hospital, still a brave old building, whose gray-stone body and mansards survive quaintly amid structures given to smart apartments and shops. Its predecessor stood near where the Michigan Avenue bridge now bestrides the river.

Rogers Park was originally a quarter-section of land which the Government sold to a hard-working Irishman named Philip Rogers. As charcoal-burner and vegetable gardener, he saved and bought more land, which in 1869 passed to his widow and to Mrs. Patrick L. Touhy, wife of another energetic Irishman, who had married into the family. Touhy built a homestead that stood for many years. It had a square tower which, to quote an early writer, “gives a view of the lovely wood that surrounds the house, and covers an area of eighty acres running eastward to the lake.”

Then or later, horse-cars achieved a laborious progress to the suburbs; stub-end cars drawn by nags all skin and bone. Eugene Field, writing in the eighties, could not resist a quip about them. As he phrased it: “The oldest house in Chicago stands on the west side and was built in 1839 A.D. The oldest horse in Chicago works for the Lake View street-car company, and was present at the battle of Marathon, 490 B.C.”

Sheridan Road was then mainly a hope, but down in a long diagonal, among the groves, ran the famous old high- way North Clark Street. It was a section of the ancient Green Bay Road, which was a toll road, with a toll-gate house at the Indian boundary line. This line lost its historic designation when it took the name of Rogers Avenue. In pioneer days it had a string of taverns. When stage-coaches began to ply upon the highway they received such titles as “ten-mile house” (at Calvary Cemetery) and “seven-mile house” (at Rosehill Cemetery), indicating the distances of those places from the Chicago City Hall. The cemeteries, it will be seen, were landmarks. There may have been few living occupants of the land; but there were plenty of dead.

Just below Calvary was a strip called for a time “No Man’s Land,” but afterward invaded by Everyman and his wife. This is the Howard Street district, which became a bright-light area with amazing speed. Rogers Park, just south of it, hums with life and with wheels. It glows feverishly at one place, where stands a prodigious movie theater, just back of which, in sharp contrast, lies a group of red- brick buildings clearly academic. This is the North Side headquarters of Loyola University, outgrowth of old St. Ignatius College. Since 1870 it has become an institution enrolling about six thousand. Only arts and sciences are taught on this North Shore campus, on whose border stands the sky-scraper building called Mundelein College. Other schools are downtown, and the high-ranking medical school is on the West Side. An unusual feature of Loyola is an administrative council that includes non-Catholics. Another thing the average university cannot claim is that half of the faculty, being Jesuit fathers, teach without pay.

It was a good while after Rogers Park was settled that there came the invasion of the forests — oak, elm, ash, and maple — which brought about the village of Edgewater. The first developers, in the eighties, were sparing of the trees, leveling only just enough to admit of streets. A few score houses went up, in a style rather favoring the Queen Anne and pseudo-Colonial types. Meanwhile, toward the west and farther south, Irving Park, also an ambitious village, was acquiring “beautiful residences.” Even in World’s Fair time it was Suburbia, with houses well apart from one another, and the city far away. “Many are the pleasures,” says our early chronicler, “which draw the Irving Parkite from his cosy fireside to the glowing grate of his neighbor.” Of course this is still true, though the grates may glow with electric flames, and the pleasures include contract bridge.

Argyle Park, in which region one may now marvel at several immense movie palaces and a monster dance-hall, had the energy of Samuel E. Gross to help it. There were gas, water, and macadamized streets in no time; also, a wonder even in the nineties, a “regular force of men to take out garbage and shovel snow.” On a westward area grew Ravenswood, whose earliest career dated back to 1868, but which had a setback in the seventies. The trouble was that an official of the Michigan Southern Railroad obligingly disposed of lots to many of his employees. When the railroad consolidated with the Lake Shore, the general offices went to Cleveland, and Ravenswood for some years was dead. It revived, however, as the city grew toward it, and became populous and eventually wholly urban.

– 3 –

It seems valuable to give these glimpses of what is now often described sweepingly as the “farther North Side.” People cling to the old names, although, to the casual eye, there is a solid stretch of streets and roofs. In a sense, the identity of villages remains. It is usually at those original centers that one finds the groups of brilliant shops, the public halls, theaters, and junctions of thronged transportation lines, to which the surrounding residents look for what they need.

But the character of the far North Side is distinct. It is a region of the apartment-dweller. One who explores it will find rather a surprising number of the good-natured, somewhat worn wooden dwellings, of the village days; he will discover stone houses of some pretensions; he will espy many a vacant lot which, for all one can tell, may be a goodly trysting-place. But, in most parts of that region the “improvements” of the modern age have consisted chiefly of buildings in which many families live together comfortably or restlessly, friends or strangers.

There is a danger of exaggerating the artificiality of life in such places. It is true that some of the flat-dwellers are birds of passage, shifting their pathetically simple furniture from Birdcage Manor to Goldfish Villa, or back again, with every spring. It is a fact that numbers of them remain tenants all their lives, never setting foot on an inch of soil that belongs to them. “The delicatessen for cuisine; the radio for education,” some one wrote. Yet there is no proof that people with these tastes, making sociologists look grave, are any worse citizens than many who have gardens and mansards of their own.

On the contrary, the number of improvement clubs, literary groups, women’s organizations, and so on, flourishing in this realm of the apartment-building is no less than elsewhere. The flaring movie house is offset by the community-house and the church. In the great high schools young people lively enough for any escapade are organized into groups that make them think, that draw them toward music and art. And parent-teacher societies are as influential here as elsewhere.

From the life in pretty flats, as from the really over-crowded districts in other parts of the city, the instinct of many people is to escape. Thousands of them come from small towns. They perch briefly in some cage — “modern apartments, one to three rooms” — until they can choose a spot on one of the enormous breezy spaces that lie so close at hand. Often whole battalions of families, whole societies of young husbands and wives, migrate together. In some suburb or far corner of the roomy city, on the plains or amid groves, they set up neat doll-houses, with lawns and avenues as spick and span as a magazine page. There in their brand-new sections they do a bit of pioneering, with plumbing that works, and with a notable habit of organizing. They have their civic associations, parent-teacher associations, dramatic clubs, new-members committee, Fourth- of-July celebration committee, and even publicity committee. The object almost seems to be to make every resident a committeeman.

Meantime there are always enough new-comers or confirmed apartment-dwellers to keep janitors busy. There are nearly 450,000 people who live east of the Chicago River and north of what is generally considered the border of the near North Side. Something like 300,000 live in wards that border the lake; while toward the west, in regions opened up within recent years, populations have doubled. Great tracts were vacant land as late as 1920. As for the situation nearer the lake, up to the nineties some of the suburban railroad trains took on board only a single passenger each morning.

– 4 –

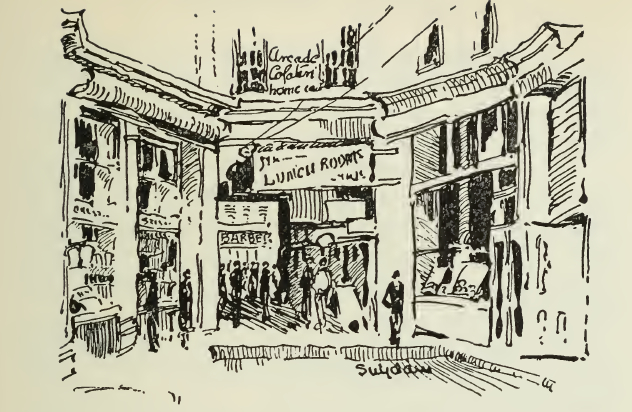

The elevated railroad system serving the northeasterly region, the interurban traversing it, the steam lines, buses, and private automobiles now convey tremendous cargoes of people daily, back and forth. Observed superficially, they seem mostly young. They are brisk, up to the minute, well enough dressed; in some cases, too well. It is a little over-wide a generalization to designate them, in a mass, as devotees of the delicatessen, the sandwich shop, the chop- suey parlor, and the beauty salon. Yet many of them must be, or there would not be such flourishing industries of that sort at the chief bright-light centers.

– + –

– + –

One of those centers, not five minutes away from the place where the poet Field lived among his trees, is Wilson Avenue, between Broadway (the old Evanston Avenue) and the lake. A slight observation would make one imagine that no staid residents cared to live thereabouts. But all kinds of people go there. One day in a recent year fifty thousand persons were counted passing the corner of Wilson and Broadway. From Wilson Avenue to Argyle, and beyond, Sheridan Road is frequented by youths with no obvious business, couples yawningly in search of new amusement, girls in garish costume, women of blase aspect, leading poodles equally blase.

“Bluff. . . . Three-room flats. . . . Instalment furniture. . . . Chop suey. . . . Life on credit.” Such are the hints thrown out by that land of streaming lights, that mob of lightsome people. Churches seek to lure them with large-lettered placards, but more amble by than go in. As a sharp observer, Ralf Gall, writes:

Boys in dogskin coats smoking dollar pipes; hatless, hoping to be mistaken for college men. Girls in high-heeled slippers, fur jackets, fur coats (they starved themselves for those coats, perhaps) in Russian boots, in light colored galoshes. They stand before the jewelry store near Broadway, and arrange themselves at the glass. They stand be- fore the music shop farther down, and do the same thing. They hesitate at the gift shop — “Well, what’s it to you?”

Wilson and Sheridan. . . . People with nothing to do but stand in the orange hut solemnly drinking orangeade. The girl in white shoves a goblet into a thing that spurts water on it ; pushes down the pump handle; and there you are — another dime gone.

North and south on Sheridan. . . . Fellows and girls; men and wives, greybeards and their mamas. Store fronts are arranged like cages for white mice, with little race tracks in and out around walls and posts. The girls pull the fellows to a standstill, and they wander about the race tracks. . . . Easter hats are out, displayed on the heads of futuristic wax models. . . . Dresses, frocks, and “formals.” Purple — Lord, what purple! Red, like salami sausage. Blotting paper green. Banana yellow. Oodles of machine lace, and sweat-shop beading and embroidery. That riding habit — “who says a girl can’t wear a derby?” And that golf outfit — m-m-m-m!

After twelve. . . . People without overcoats hurry into the eat shop on Clarendon avenue. (Gene Field’s house was a few blocks south.) They buy ham, dill pickles, cream, and a half pound of coffee. Goin’ to be a little party up in Eddie’s room. . . . High school kids just from a dance crowd into the waffle shop, where white- jacketed fellows are frying waffles right in the window. . . . Throngs pour out of the great dance hall. Pumpkin-colored cabs block traffic. Coppers cuss.

If it be summer, along the beaches from north to south, Lawrence avenue, the old Wilson beach, Clarendon, Buena avenue, Hogan’s alley, boys and girls arrive from all over the North Side in cars. Or, if they live in the furnished rooms of the Wilson avenue district, they walk along the streets in bath-robes. . . . Boys and girls light fires and sit around them, occasionally chirping up in sentimental song. A piece of roofing-iron keeps off the wind. Driftwood is flung on. The sparks fly. . . . The lake, with its curl of white, rolls dark and dreamlike before them. . . .

Many a sociologist, who might scorn such vignettes as meaning nothing, has studied Uptown Chicago — to use its commercial name — and has both marveled at its sudden growth and analyzed its types. These scientists have found the city a rich laboratory, and in the Wilson Avenue district they observe a center of fragile domesticity, of married couples both members of which earn pay-checks, of women in defiant independence. Children are relatively few. Both husband and wife have their main interests outside the home. The families thus emancipated live, and prefer to live, in rooming-houses, in kitchenette apartments, in residential hotels. Over the portals of any number of the buildings of old Buena Park one sees signs offering such miniature “homes,” sometimes with emphasis on the presence of “sleeping-rooms,” and often adding, as a great inducement, “shower-baths.”

Ernest R. Mowrer, of the University of Chicago, published in 1925 a study which found that there were sixty-eight divorced for every one thousand population in the Wilson Avenue district. He mentioned as underlying causes what he called the “restlessness of women” and the “romantic complex.” Mr. Mowrer’s data have since found support in court records which show that in a summer month of 1930 the divorces in the Forty-eighth ward, approximately the region Mowrer studied, reached the number of twenty-one, the largest proportion in the city. It is interesting to add that the same statistics show no divorces at all in a West Side ward, the Thirty-first, and a striking decrease in divorce figures all over the West Side, as compared with those of the North Side. But desertions — that is another story.

– 5 –

A half-mile north of Wilson Avenue is a newer district vividly suggesting prosperity, a more solid kind. A huge bank building stands there to prove the case. There were close to five million dollars of savings deposits in that bank a year or so ago. Giant movie houses and other industries furnish a gaudy glow upon the intersection of the impressive streets, Lawrence Avenue and Broadway. On the street-cars of these streets ride sixty thousand, seventy thousand, even a hundred thousand people some days. West of the L, life grows quieter, an air of suburb returns. The staid citizen whom it was hard to find at Wilson and Sheridan hurries to his stone-front dwelling, turning his back on the array of delicatessens and beauty-shops.

A half-mile north of Wilson Avenue is a newer district vividly suggesting prosperity, a more solid kind. A huge bank building stands there to prove the case. There were close to five million dollars of savings deposits in that bank a year or so ago. Giant movie houses and other industries furnish a gaudy glow upon the intersection of the impressive streets, Lawrence Avenue and Broadway. On the street-cars of these streets ride sixty thousand, seventy thousand, even a hundred thousand people some days. West of the L, life grows quieter, an air of suburb returns. The staid citizen whom it was hard to find at Wilson and Sheridan hurries to his stone-front dwelling, turning his back on the array of delicatessens and beauty-shops.

Yes, viewed as a whole, Uptown Chicago probably merits its boast of being the shopping center of a million.

A sanguine view of it, or what might be called a semi-official version, runs like this:

The spirit of Chicago, typified in its well-earned motto of “I Will,” has nowhere been better exemplified than in that section which lies to the north, approximately bounded by Argyle, Clark, Montrose and the lake. Here is a community complete in itself, within whose borders one could live quite satisfactorily and never step beyond them. Though but a section of a city, it has in itself every accessory of a city — delightful places in which to live, dozens of smart and utilitarian shops, great churches and strong banks, and every imaginable form of entertainment.

Yet an academic writer was so hasty as to assert that, in Chicago, everything converged toward the Loop!

– + –

+